The southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius) is one of the world’s largest flightless birds and a key ecological force in the tropical rainforests of northern Australia, New Guinea, and nearby islands. Recognizable by its tall casque and vivid skin tones, this elusive bird plays a vital role as a seed disperser for hundreds of plant species. Despite its impressive stature and strength, the southern cassowary faces a range of threats in the wild, making its conservation increasingly urgent.

| Common name | Southern cassowary |

| Scientific name | Casuarius casuarius |

| Alternative names | Australian cassowary, double-wattled cassowary, two-wattled cassowary |

| Order | Casuariiformes |

| Family | Casuariidae |

| Genus | Casuarius |

| Discovery | First described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 |

| Identification | Large, flightless bird with glossy black plumage, vivid blue and red skin on neck and head, and a prominent helmet-like casque |

| Range | Native to northern Australia, New Guinea, and surrounding islands |

| Migration | Non-migratory; highly territorial and sedentary within its habitat |

| Habitat | Dense tropical rainforest, especially lowland and swamp forest; also occurs in secondary and fragmented forests |

| Behavior | Solitary and territorial; males are highly aggressive during nesting and chick-rearing; fast and capable of powerful kicks; plays a key ecological role as a seed disperser |

| Lifespan | Typically 18-20 years in the wild; over 40 years in captivity; rare captive records over 60 years |

| Diet | Primarily frugivorous; consumes over 200 plant species; occasionally eats fungi, invertebrates, and small vertebrates |

| Conservation status | Least Concern (IUCN); Australian population listed as Endangered under EPBC Act |

| Population | Estimated 20,000-50,000 mature individuals globally; around 5,000 birds in Australia |

Discovery

The southern cassowary has been known to Indigenous peoples of New Guinea and northern Australia for millennia, and was familiar to early traders across the Malay Archipelago long before it entered European science. The name “cassowary” derives from the Malay “kesuari,” likely rooted in the Papuan terms “kasu” (horned) and “weri” (head), referencing the bird’s prominent casque. This etymology reflects a long-standing regional awareness of the species, as cassowaries were traded throughout island Southeast Asia, particularly after the Portuguese conquest of Malacca in 1511, which intensified maritime exchange routes where Malay was the lingua franca.

The first documented arrival of a live southern cassowary in Europe occurred in 1597, during the inaugural Dutch expedition to the East Indies led by Cornelis de Houtman. The bird was captured on Seram Island (in the Moluccas) and gifted to the Dutch by a Javanese prince. It eventually reached the Netherlands, where it lived in elite circles until its death in 1607. By the 17th century, cassowaries had become well-known among European elites, often appearing in menageries and exotic animal collections. Chinese interest is also recorded from this period: in 1774, Emperor Qianlong of the Qing dynasty commissioned artistic renderings and verse celebrating the bird, reflecting its symbolic and aesthetic value across cultures.

The formal scientific description of the southern cassowary was provided by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, who placed it within the genus Struthio, grouping it with ostriches and rheas, as Struthio casuarius. However, Linnaeus had earlier introduced the genus Casuarius in the 1748 edition of Systema Naturae, though this name was omitted in his more widely accepted 10th edition, which marks the starting point for zoological nomenclature under ICZN rules. Consequently, the genus Casuarius is officially attributed to Mathurin Jacques Brisson, who re-established it in 1760. The southern cassowary is now recognized as the type species of the genus Casuarius.

Numerous scientific names have historically been applied to the species, reflecting confusion due to individual variation and the effects of age and skin color fading in preserved specimens. Several subspecies were described, but these remain difficult to verify given the low number of specimens, the effects of trade and relocation by local peoples, and the bird’s naturally variable morphology.

The Australian population of the southern cassowary was first recorded during Edmund Kennedy’s 1848 expedition in northern Queensland. Botanist William Carron documented the bird after a specimen was shot by Jackey Jackey (Aboriginal Australian guide), although it was later lost. The species was described as Casuarius australis by William Sheridan Wall in 1854. Though sometimes credited to John Gould, who published on the species in 1857 and 1865, Gould himself acknowledged Wall’s earlier authority. In subsequent years, alternate names such as Casuarius johnsonii were proposed, but later synonymized with C. casuarius.

Identification

The southern cassowary is a large, flightless bird with coarse, black bristle-like plumage and a vivid, bare-skinned head and neck – features that contribute to its reputation as one of the world’s strangest-looking birds. The casque, a prominent helmet-like structure on the crown, is brown and ranges from 13 to 17 centimeters (5.1-6.7 inches) in height. The front of the face, from the eyes to the base of the bill, is dark, while the sides and back of the head and neck are bright blue, with the nape (back of the neck) colored deep red. Two long, fleshy, red wattles, up to 17.8 centimeters (7.0 inches) in length, dangle from the throat.

The legs are thick and extremely powerful. Each of the three toes bears a claw, but the inner toe carries a large, sharply pointed claw up to 12 centimeters (4.7 inches) in length, which can be used defensively and is capable of causing serious injury.

Sexual dimorphism is expressed primarily through size and structure rather than color. While plumage is similar between sexes, females are larger, with a more prominent casque, a broader bill, and more vividly colored skin on the head and neck.

The southern cassowary is the third-tallest and third-heaviest bird species in the world, following the common ostrich (Struthio camelus) and Somali ostrich (Struthio molybdophanes). Adults typically stand between 1.50 and 1.80 meters (4.9-5.9 feet), though large individuals can reach up to 1.9 meters (6.2 feet). Weight varies widely: females average around 60 kilograms (132 pounds), males between 30 and 35 kilograms (66-77 pounds), and the heaviest recorded individuals may weigh up to 85 kg (187.4 pounds).

Juveniles hatch covered in brown-striped down, which provides camouflage in the forest understory. As they grow, their plumage gradually darkens and becomes coarser. Juveniles typically retain their streaked appearance for the first 6 to 12 months. By around 2 to 3 years of age, they acquire the black adult plumage and fully developed casque, although body size and skin coloration may continue to develop until maturity at approximately 3 to 5 years of age.

Vocalization

The southern cassowary produces a variety of vocalizations, including some of the lowest-frequency sounds known in birds. Its signature call is a deep, booming note made up of rhythmic pulses, typically heard during the breeding season. These calls can reach frequencies as low as 32 Hz, hovering at the threshold of human hearing. At close range, the sound is not only audible but often felt as a low vibration, giving it a powerful presence in the forest.

Outside the mating season, cassowaries emit rumbling and hissing calls, likely used in close-range communication or defensive contexts. The function of these sounds remains poorly studied but may play a role in territorial signaling or threat displays. Observations suggest that booming calls are produced through neck inflation and specialized posture, with the skin at the back of the neck visibly expanding during vocalization.

Chicks produce high-pitched whistles and chirps to maintain contact with the attending male, who provides all parental care. These frequent contact calls are critical for chick survival in the dense undergrowth of rainforest habitat.

The southern cassowary’s use of low-frequency sound may be an evolutionary adaptation for long-range communication in dense tropical forest, where visual contact is limited and higher-pitched sounds attenuate quickly.

Range

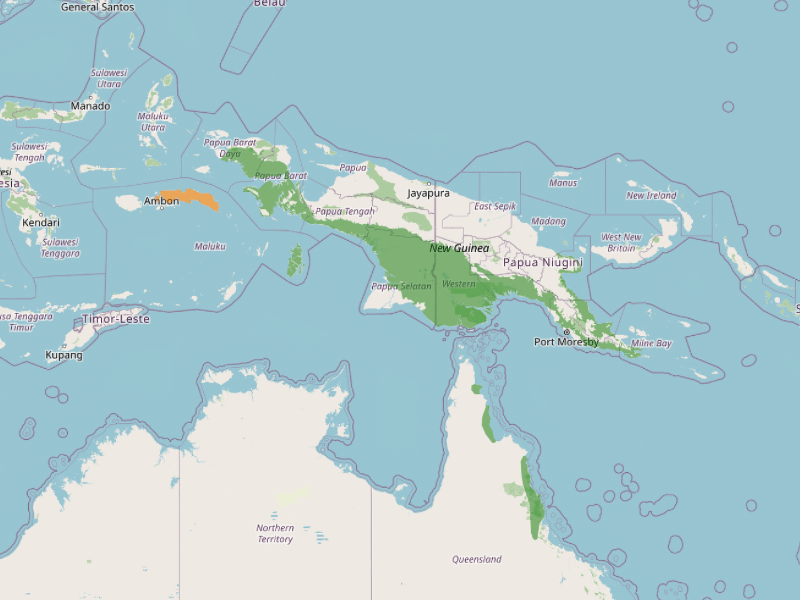

The southern cassowary is native to the tropical lowlands of New Guinea (including Papua, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea), the Aru Islands, and north-eastern Australia. It is also present on Seram Island, where it is believed to have been introduced through trade. In New Guinea, the species is widespread across southern and central regions but is largely absent from the northern watershed stretching from the Bird’s Head Peninsula to the Huon Peninsula.

In Australia, it occurs only in Queensland, where three distinct subpopulations are recognized: a large southern population extending from the Paluma Range north of Townsville to Mount Amos, and two smaller populations in the McIlwraith Range and the Apudthama National Park on Cape York Peninsula.

Migration

The southern cassowary is a sedentary and territorial species. It does not undertake any form of seasonal or long-distance migration. Individuals maintain relatively stable home ranges throughout the year, although they may shift activity within their territory in response to the seasonal availability of fruiting trees. Movements are generally local and restricted to within suitable forested habitat.

Habitat

The southern cassowary is primarily a rainforest specialist, occurring most frequently in lowland tropical forests. In New Guinea, it typically inhabits elevations below 500 meters (1,640 feet), though it can be found up to 1,100 meters (3,600 feet), and occasionally as high as 1,400 meters (4,600 feet) in Australia. The species also uses a range of adjacent habitats, including savanna forests, mangrove stands, and even fruit plantations, particularly where these are near forested areas.

In Australia, cassowaries are largely confined to fragmented rainforest remnants, often surrounded by human development. Their distribution is patchy, with population density ranging from 0.04 to 1.8 birds per square kilometer depending on habitat quality and connectivity. In contrast, cassowaries in New Guinea occupy more extensive tracts of primary and secondary forest and tend to occur at higher densities, particularly in areas with limited human disturbance.

Their reliance on forested environments, particularly for access to fruiting trees, makes them vulnerable to habitat loss and fragmentation. Even brief incursions into modified or open areas tend to be limited, highlighting the species’ dependence on dense, fruit-rich rainforest ecosystems for both food and shelter.

Behavior

The southern cassowary is a solitary and secretive bird, active primarily during the day and foraging alone on the rainforest floor. It follows well-worn paths through dense vegetation and is highly territorial. Interactions with other cassowaries are typically limited to disputes over territory.

Although generally shy, the southern cassowary can be dangerously aggressive when provoked or habituated to human presence. It is capable of rapid acceleration, high leaps, and powerful kicks with its heavily muscled legs. Cassowaries are also among the fastest-running birds, able to sprint at speeds up to 50 km/h (31 mph) through dense undergrowth when fleeing threats or chasing rivals. Each foot bears a long, dagger-like claw on the inner toe that can inflict serious injury. Cassowaries use a range of displays to warn intruders: upright strutting, fixated stares, preening, and booming or hissing vocalizations. If these signals are ignored, the bird may charge, shove, or leap and kick in self-defense or when defending chicks.

Despite its formidable reputation, confirmed fatal attacks on humans are extremely rare. Since 1900, only two human deaths have been conclusively linked to southern cassowary attacks: one in Australia in 1926, when a boy attempted to kill a cassowary and was fatally kicked, and another in Florida in 2019, when a captive bird killed its owner after he fell. A study of 221 cassowary attacks revealed that most incidents involved birds that had been habitually fed by humans, and many were motivated by food expectation rather than unprovoked aggression.

The increasing overlap between cassowary habitat and human settlements, often driven by feeding or habitat encroachment, has heightened risks for both species. Habituated cassowaries are more likely to cross roads or enter residential areas, where they face higher mortality and pose potential dangers to people.

Breeding

Southern cassowaries are sequentially polyandrous, with females mating with multiple males over the course of a breeding season. Pair bonds are short-lived and typically dissolve shortly after copulation. The breeding season occurs during the austral winter to early spring (June to November), coinciding with peak fruit availability.

Courtship begins with the male producing deep booming calls and displaying increased social and spatial interest in nearby females. In successful encounters, this is followed by tactile behaviors such as rubbing necks and brief following or circling. After mating, the female departs to find another partner, while the male assumes full responsibility for incubation and chick rearing. Sexual maturity is typically reached by 2-3 years of age, with breeding occurring well into adulthood, and occasionally beyond 30 years.

The male prepares a nest on the ground, consisting of a mat of herbaceous vegetation, approximately 5-10 centimeters (2-4 inches) thick and up to 100 centimeters (3.3 feet) wide. This structure facilitates moisture drainage, which is essential in tropical rainforest environments. The female lays a clutch of 3-4 large, granulated, bright pea-green eggs, each measuring around 138 x 95 millimeters (5.4 x 3.7 inches). Once laying is complete, the female is typically driven off by the male, who then becomes increasingly protective of the nest site.

Incubation is performed exclusively by the male and lasts approximately 47-61 days. The chicks hatch fully feathered and precocial, able to walk and follow their father almost immediately, but remain dependent on him for guidance and protection. During this extended parental care phase, lasting about 9 months, the male leads the chicks through the forest, teaches them to forage, and defends them aggressively from potential threats.

Chicks may occasionally feed on ectoparasites found on the male or consume his feces as a source of gut flora and nutrients. Once the juveniles become independent, the male ceases his parental role and the group disperses.

Lifespan

Southern cassowaries typically live 18-20 years in the wild, while individuals in human care can reach 40 years or more. The difference is due to reduced risks in captivity, such as protection from predators, consistent food supply, and veterinary care.

Although no formal longevity records exist for wild birds, anecdotal accounts suggest that cassowaries in undisturbed areas can sometimes live up to 40 years. In captivity, they are known to be remarkably long-lived. One bird at Healesville Sanctuary lived for at least 48 years, and another was estimated to have reached over 61 years. These cases indicate that, under ideal conditions, the species is capable of exceptional longevity. However, in the wild, environmental pressures and anthropogenic threats generally limit their lifespan.

Mortality factors

The main causes of cassowary mortality in the wild are related to human activity. A study of 140 recorded deaths from 1986 to 2004 found that 55% were due to vehicle collisions, making it the single leading cause. Dog attacks accounted for 18%, with both causes responsible for 74% of all known deaths. Mortality is especially concentrated in the Mission Beach region (Queensland), where 63% of all recorded deaths occurred, highlighting severe local pressures. Habitat loss and fragmentation increase the likelihood of encounters with roads and domestic dogs, further elevating mortality risk.

Diet

Southern cassowaries are primarily frugivorous, with fallen fruit forming the bulk of their diet. However, they are also opportunistic omnivores and will consume a variety of other items including fungi, small vertebrates, invertebrates, carrion, and plant material. Across their range, over 238 plant species have been documented in their diet, highlighting their diverse foraging habits and critical role in rainforest ecology.

These birds are uniquely adapted for seed dispersal. They swallow fruits whole, including many large-seeded species that are too big for most other frugivores to consume. The seeds pass through the digestive tract largely undamaged and are deposited in nutrient-rich piles of dung that often contain hundreds or even thousands of seeds. In some cases, passage through the cassowary’s gut is necessary for seed germination. Their droppings not only help fertilize the seeds but also attract small mammals such as white-tailed rats, melomys, and musky rat-kangaroos, which may further assist in seed dispersal. As the only large-bodied frugivore in Australia’s tropical rainforests, the southern cassowary plays an irreplaceable role in maintaining the plant diversity and long-distance seed dispersal that sustains these ecosystems.

Field studies conducted in North Queensland show that cassowaries do not feed randomly but exhibit seasonal shifts in fruit preference. During periods of fruit scarcity (May-July), they rely heavily on a subset of plant species that fruit continuously year-round. In the peak fruiting months (October-December), their diet becomes more diverse and includes more species that fruit annually or biennially. Interestingly, fruit traits such as size, colour, or moisture content did not predict dietary inclusion, though large-seeded fruits were significantly overrepresented in the diet.

Recent telemetry-based research confirms that cassowaries continue to function as key seed dispersers even in fragmented rainforest habitats. Birds living near urban areas incorporate exotic fruits into their diet, sometimes up to 30%, yet still consume a wide variety of native fruits and remain active dispersers across fragmented landscapes. These individuals tend to be more active and mobile, foraging between gardens and remnant rainforest patches. Their flexible foraging strategy enables them to persist despite habitat degradation, and their ecological function as seed dispersers remains intact.

Culture

The southern cassowary holds profound cultural significance for many Aboriginal communities across the Wet Tropics and Cape York Peninsula in northern Queensland. For rainforest peoples, the cassowary is not only a source of food, but also a creature woven into stories, ceremonies, songs, and dances passed down through generations. Its feathers, claws, and bones have historically been used for ornamentation and hunting tools, and the bird itself is revered as a totemic animal and forest guardian.

One of the most well-known Aboriginal Dreamtime stories tells of how the cassowary got its helmet (casque). In this tale, the cassowary was mocked for being flightless and ran into a rock, which stuck to its head. Later, the cassowary redeemed itself by courageously defending the other animals from snakes, becoming a symbol of protection. From that day forward, the cassowary became the fearless protector of the rainforest – a role it symbolically maintains to this day.

The cassowary may also have influenced broader Australian mythology. In a 2017 article for Australian Birdlife, Karl Brandt proposed that Aboriginal encounters with the southern cassowary inspired early descriptions of the bunyip, a mysterious creature from settler folklore. The first written account of the bunyip in 1845 described it as laying large pale blue eggs, possessing deadly claws, a bright chest, powerful hind legs, and an emu-like head – all features shared with the cassowary. Additionally, the serrated bill described in the myth may reflect associations with stingray barbs and the traditional weapons of Aboriginal groups in Far North Queensland, who live within the cassowary’s native range.

Together, these stories reflect the cassowary’s dual role in Indigenous cultures as both a respected ancestral figure and a source of mythic inspiration – a creature both real and legendary.

Threats and conservation

The southern cassowary is currently listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List due to its extensive range across northern Australia and New Guinea and its stable global population trend. The total number of mature individuals is conservatively estimated between 20,000-50,000, though this figure may be higher, with the vast majority residing in New Guinea. In Australia, the population is far smaller and more fragmented, with recent estimates suggesting around 4,000 to 5,000 individuals.

Despite the global status, the Australian population remains under significant pressure and is listed as Endangered under the national Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC). Within Queensland, its northern population is currently assessed as Vulnerable, while the southern population retains Endangered status under the Nature Conservation (Animals) Regulation 2020.

Threats

The most severe historic threat to the Australian population was habitat loss, which had caused rapid declines prior to the protection of much of the bird’s rainforest range under World Heritage legislation in 1988. Though numbers have stabilized since then, fragmentation of remaining habitat continues to limit population growth. Motor vehicle collisions and dog attacks remain the primary direct causes of cassowary mortality, especially in developed areas such as Mission Beach, where roads and urban sprawl intrude on cassowary territories. From 1986 to 2004, over half of all confirmed deaths in Queensland were due to vehicle strikes, and nearly a fifth were caused by dog attacks. The threat posed by vehicles tends to increase significantly following cyclonic events, when cassowaries are displaced in search of food.

In New Guinea and Indonesia, the southern cassowary remains widespread, but it faces significant pressure from hunting and local trade, particularly in areas near human settlements. The species is highly valued as a food source and in traditional ceremonies, including bride price transactions. Hunting is unsustainable in some regions and has already led to local extirpations. Although logging in remote areas appears to have had a limited effect on hunting intensity, the expansion of roads and infrastructure, combined with potential habitat conversion for palm oil plantations, could increase risks in the future. Cassowaries are notably less common in logged and foothill forests, emphasizing their dependence on undisturbed lowland rainforest.

Conservation efforts

Conservation efforts in Australia have included the implementation of a national recovery plan, habitat restoration and revegetation projects, establishment of temporary feeding stations after cyclones, and public awareness campaigns. Most remaining habitat is now within protected areas, and community-based monitoring and wildlife crossings have been promoted to reduce road mortality. Programs targeting feral pig and dog control are also active in areas with high cassowary density.

Proposed conservation actions focus on better population monitoring and demographic research, especially across its New Guinea range, where little systematic data exist. In Australia, ongoing research is recommended to assess the long-term impact of cyclones, fragmentation, traffic, and disease, and to refine strategies for habitat connectivity. There is also interest in exploring translocation as a management tool for injured or displaced individuals.

Although southern cassowaries have been successfully bred in zoos around the world, including facilities such as White Oak Conservation in Florida, their continued survival in the wild will depend heavily on preserving intact rainforest habitat and mitigating human-induced threats.

Similar species

The southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius) shares its genus with two other cassowary species, both native to New Guinea, and is often compared to the emu, another large flightless bird native to Australia. While all are ratites and share certain ecological traits, they differ notably in appearance, range, and behavior.

Northern cassowary (Casuarius unappendiculatus)

This species is found in the lowland rainforests of northern New Guinea and differs from the southern cassowary by having a single, rather than double, throat wattle. Its casque is slightly taller and more compressed, and its bare facial skin tends to be more bluish. While behaviorally similar, it appears to tolerate slightly more open habitats than its southern relative.

Dwarf cassowary (Casuarius bennetti)

The smallest of the cassowaries, the dwarf cassowary inhabits mountainous forest regions in New Guinea and New Britain. It lacks wattles altogether, has a shorter casque, and is generally more cryptic and elusive. Compared to the southern cassowary, it prefers higher elevations and displays more secretive behavior, making it less frequently observed.

Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

Unlike cassowaries, the emu is native to the open woodlands and grasslands of mainland Australia and lacks a casque or any facial ornamentation. It is taller but lighter-built, with shaggy brown plumage and long, bare legs. Emus are more social and nomadic, often forming loose flocks, and they thrive in more arid environments than the rainforest-dwelling cassowary.

Future outlook

The southern cassowary faces a complex future shaped by both longstanding threats and emerging conservation opportunities. Globally, the species is not currently considered at risk, thanks to its wide range and stable populations across much of New Guinea. However, in Australia, particularly in the tropical rainforests of Queensland, its future remains more precarious. Despite some recovery since the 1980s and increasing legal protection, the Australian population is still fragmented and vulnerable to habitat loss, road mortality, dog attacks, and the impacts of cyclones and climate change.

Encouragingly, decades of conservation action, including habitat protection, ecological research, and community engagement, have helped stabilise numbers in some regions. Ongoing efforts to protect remaining forest corridors, reduce human-wildlife conflict, and strengthen monitoring are critical to ensuring long-term persistence. The southern cassowary’s ecological role as a keystone seed disperser highlights the broader significance of its conservation: safeguarding this species supports the regeneration and diversity of entire rainforest ecosystems. With continued investment and public support, the future of the southern cassowary in both Australia and New Guinea can remain secure.

Further reading