The kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) is one of the most evolutionarily distinct and critically endangered birds in the world. Endemic to New Zealand, it is the only extant species of its genus and one of just three surviving members of the ancient parrot superfamily Strigopoidea. A flightless, nocturnal herbivore with unusually long lifespan and lek-based breeding, the kakapo combines a suite of rare traits found in no other bird.

Formerly widespread across both main islands of New Zealand, it suffered a catastrophic decline following human arrival and the introduction of mammalian predators. Today, fewer than 250 individuals remain, placing it among the rarest extant bird species worldwide. The species’ ongoing recovery represents one of the most complex and closely monitored conservation efforts in modern ornithology.

| Common name | Kakapo |

| Scientific name | Strigops habroptilus |

| Alternative name | Owl parrot or owl-faced parrot |

| Order | Psittaciformes |

| Family | Strigopidae |

| Genus | Strigops |

| Discovery | First formally described by George Robert Gray in 1845; known to Maori for centuries prior |

| Identification | Large, flightless parrot with moss-green, mottled plumage; facial disc, stout beak, strong legs, and musty odor; males up to 4 kg |

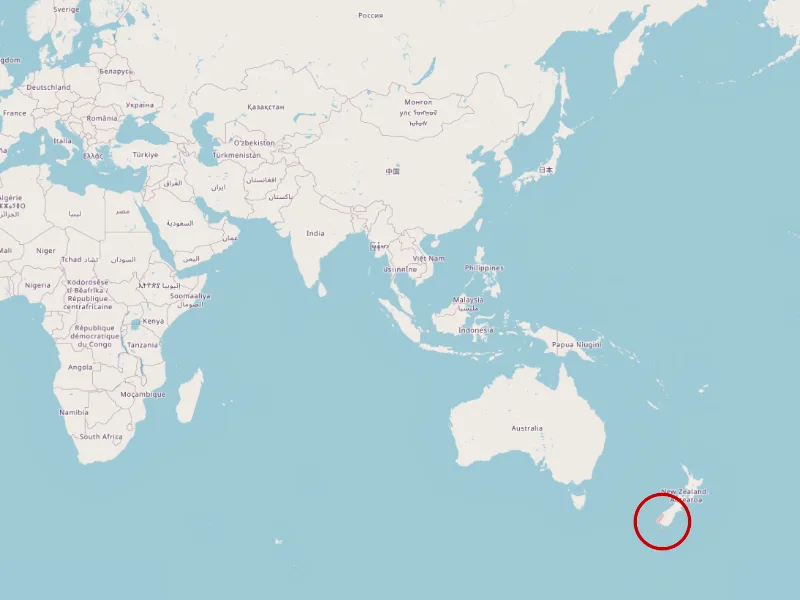

| Range | Endemic to New Zealand; now restricted to predator-free offshore islands and fenced sanctuaries |

| Migration | Non-migratory; maintains stable year-round home ranges |

| Habitat | Prefers rimu-dominated forest and regenerating scrub on predator-free islands; historically a habitat generalist |

| Behavior | Nocturnal and solitary; excellent climber; males display at leks with booming calls; females raise young alone |

| Lifespan | Average lifespan around 60 years; possibly over 100 in ideal conditions |

| Diet | Herbivorous; feeds on native leaves, fruits, seeds, bark, and rimu mast during breeding years |

| Conservation status | Critically Endangered (IUCN) |

| Population | 242 individuals as of 2025; all managed; intensively monitored under the Kakapo Recovery Programme |

Discovery

The kakapo was first formally described in 1845 by English ornithologist George Robert Gray, who recognized it as a distinctive species unlike any other parrot known at the time. In doing so, he established a new genus, Strigops, and assigned the binomial name Strigops habroptilus. Gray, however, was uncertain about the exact origin of the specimen he examined and vaguely attributed it to “one of the islands of the South Pacific Ocean.” Later taxonomic consensus designated Dusky Sound, on the southwest coast of New Zealand’s South Island, as the official type locality.

The name Strigops habroptilus combines roots that reflect the bird’s physical appearance. Strigops derives from the Ancient Greek words strix (genitive strigos), meaning “owl,” and ops, meaning “face,” referring to the bird’s large, forward-facing eyes and facial disc reminiscent of owls. The specific epithet habroptilus comes from habros (“soft”) and ptilon (“feather”), an allusion to the bird’s unusually fine, mossy-textured plumage.

Although formally described in the mid-19th century, the kakapo was long known to the Maori, the Indigenous people of Aotearoa (New Zealand). The name “kakapo” is derived from Maori words kaka (parrot) and po (night), reflecting both its parrot lineage and nocturnal habits. This name is used in both singular and plural form and is increasingly written with macrons in New Zealand English to reflect proper pronunciation.

Since its scientific recognition, the taxonomy of the kakapo has remained relatively stable. The species is monotypic, with no subspecies recognized. A minor nomenclatural debate emerged in the 20th century regarding the gender agreement of the species epithet. In 1955, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature ruled that the genus Strigops is feminine, leading some taxonomists to use habroptila. However, a 2023 review by J. L. Savage and A. Digby argued for the retention of the original masculine form habroptilus in accordance with current ICZN rules – a position widely adopted in 2024 by both the International Ornithological Congress and the eBird/Clements Checklist.

Modern genetic and phylogenetic research has revealed that the kakapo belongs to an ancient and distinct lineage within the order Psittaciformes. It is placed in the family Strigopidae, alongside the two species of the genus Nestor – the kea (Nestor notabilis) and the kaka (Nestor meridionalis). These three parrots are endemic to New Zealand and together form a basal clade that diverged from all other parrots approximately 33-44 million years ago. The kakapo itself diverged from its Nestor relatives around 27-40 million years ago, according to molecular clock estimates.

Early ornithologists had speculated on a possible kinship between the kakapo and Australian ground parrots due to shared terrestrial habits and cryptic green coloration. However, DNA studies have shown that this similarity is convergent, not phylogenetic – an independent adaptation to ground-dwelling life in dense vegetation.

Further deep genomic research, conducted by the Vertebrate Genomes Project, has positioned the kakapo as one of the first endangered bird species with a chromosome-level reference genome. The genome revealed 23 chromosomes and an unusually high level of inbreeding, with an inbreeding coefficient (F_ROH) of approximately 53% – among the highest recorded in any vertebrate.

Despite such bottlenecks, analyses suggest that natural purging of deleterious alleles may have helped reduce mutational load. These insights underscore both the evolutionary distinctiveness of the species and the complexity of managing its future genetic health.

Identification

The kakapo is the heaviest living parrot and among the largest flightless birds in terms of body length. Adults measure 58-64 centimeters (22.8-25.2 inches) in length and have a wingspan of approximately 82 centimeters (32.3 inches), though the wings are not used for powered flight. Body weight varies significantly, typically ranging from 1 to 4 kilograms (2.2 to 8.8 pounds). The species is unusually heavy for a parrot and capable of storing substantial fat reserves. Individuals can gain up to 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) of fat prior to the breeding season.

The kakapo is instantly recognizable by its moss-green plumage mottled with yellow and black, a coloration that provides effective camouflage in native forest vegetation. The upperparts are more heavily barred or speckled, while the underparts tend to be yellower with subtle streaking. The feathers are soft and lack the stiffness required for flight, giving the bird a plush, velvety appearance.

Most striking is the pale facial disc, framed by fine feathers that give the kakapo an owl-like expression – an unusual trait among parrots that earned it the early nickname “owl parrot” and contributes to its reputation as one of the world’s weirdest-looking birds. The beak is ivory to bluish-grey, often surrounded by feather-like vibrissae. The eyes are dark brown, and the feet are large, zygodactyl (two toes forward, two backward), with strong claws adapted for climbing.

Sexual dimorphism is present but relatively modest. Males are consistently larger than females: adult males typically weigh around 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds), while females average 1.5 kilograms (3.3 pounds). Females are more slender overall, with a narrower head, more tapered beak, and slimmer, pinkish-grey legs and feet. The facial disc is also narrower, and their plumage tends to be slightly duller, with less yellow and barring than in males. During breeding, females develop a brood patch – a bare area on the belly for incubating eggs, which is absent in males.

Juvenile kakapo hatch with greyish-white down, through which their pink skin remains visible for several weeks. As they grow, they gradually develop plumage that is duller and less yellow than that of adults, with more uniform black barring. Juveniles can also be recognized by their shorter wings, tail, and beak, as well as a temporary ring of fine feathers around the eyes that resembles eyelashes. Full feathering is typically achieved by 70 days post-hatch, though color saturation and body proportions continue to develop beyond that point.

The species is also known for its distinctive musty-sweet scent, a trait that can unfortunately make them more detectable to predators.

Vocalization

The kakapo has a rich and unusual vocal repertoire, especially for a nocturnal and largely solitary bird. While generally quiet outside of the breeding season, vocal activity increases dramatically during courtship, when males gather at traditional lek arenas (track-and-bowl systems) where they produce deep, resonant booming calls that can travel for several kilometers.

Listen to the kakapo’s booming call:

These low-frequency (<100 Hz), non-directional booms are typically repeated for hours each night across a breeding period that may last up to three months. The sound is generated using specialized air sacs, and is accompanied by a second courtship call known as the ching – a nasal, metallic, high-pitched note (2-5 kHz) repeated at roughly one-second intervals. The ching is more directional and is thought to help guide females toward the calling male.

Outside the breeding season, kakapo are much less vocal, but still produce a range of sounds. Both sexes emit a sharp, high-pitched skraak, often used in alarm, territorial displays, or agonistic interactions.

Listen to the kakapo’s skraaking call:

Additional calls include pig-like grunts, duck-like warks, donkey-like braying, and drawn-out croaking distress calls, the latter especially common in handled females and juveniles. Fiordland males have been reported to produce an even broader range of vocalizations, including hisses, screeches, screech-crowing, low-amplitude humming, and mechanical beak-clicking.

Perhaps the most unusual vocalizations have come from Sirocco, a hand-raised male imprinted on humans. When near people, he has been recorded producing quiet, breathy “muttering” sounds – low-frequency syllables rich in harmonics that resemble human vocal tone and cadence more than typical bird calls. These sounds often occur when he is being gently touched or spoken to, and occasionally include soft ching-like notes.

Although the origin of these calls likely stems from early-life exposure to human speech, their exact function remains unknown. No other kakapo have been documented producing similar “mutterings,” and steps have since been taken to reduce imprinting in captive-reared chicks.

Despite their acoustic richness, kakapo remain understudied bioacoustically, and no comprehensive quantitative analysis of their vocal behavior has yet been published. However, field reports note that loud environmental sounds, like thunder, avalanches, or sudden animal calls, can trigger spontaneous vocal responses. Audio playbacks may also elicit calling in wild individuals. Given their complex courtship acoustics, rare vocal mimicry, and variation across regions and individuals, kakapo vocalizations represent a valuable area for future research.

Range

Before human settlement, the kakapo was widespread across mainland New Zealand, including both the North and South Islands. Subfossil remains and archaeological records, such as Maori food middens, suggest it was once among the country’s most common birds, inhabiting a broad array of ecosystems. Though not initially confirmed from fossil evidence, it likely colonized Stewart Island/Rakiura prior to European arrival.

By the 20th century, habitat loss, hunting, and the introduction of mammalian predators had eliminated kakapo from nearly all of its original range. The last natural populations survived in the wetter, more remote regions of Fiordland and Stewart Island, but these too declined rapidly due to cat predation. Since the late 1980s, all known individuals have been translocated to managed sites.

Today, the kakapo exists only on protected offshore islands and within a fenced mainland sanctuary, all of which are intensively managed for predator exclusion. These include:

- Codfish Island / Whenua Hou (1,396 ha), off the coast of Stewart Island – the primary breeding site and center of Kakapo Recovery.

- Anchor Island (1,140 ha), in Fiordland’s Dusky Sound – a rimu-rich island with periodic mast-fruiting that supports breeding.

- Little Barrier Island / Hauturu-o-Toi, in the Hauraki Gulf – another predator-free forested refuge.

- Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari (3,400 ha), a fenced mainland site in the Waikato region, where a small population of males was reintroduced in 2023 as a trial for potential mainland re-establishment.

Migration

The kakapo is a non-migratory species. Individual birds maintain stable home ranges, which vary from as small as 1.8 ha to over 50 ha, depending on factors such as age, sex, rearing history, and season. Juveniles typically occupy larger ranges than adults, possibly due to exploratory behavior or different nutritional requirements. Seasonal tracking studies have shown that home ranges are smallest in winter, when kakapo are less active.

Although traditionally described as solitary, some individuals, particularly juveniles and non-breeding birds, have been observed roosting near one another, suggesting flexible social spacing outside the breeding season.

Habitat

Historically, the kakapo was a habitat generalist, inhabiting environments ranging from lowland podocarp-broadleaf forests to beech stands, tussock grasslands, and coastal scrub. The species was highly adaptable, capable of surviving in both the dry, warm conditions of the North Island and the cold, subalpine forests of Fiordland. Areas of regenerating landslip vegetation, often rich in fruit-bearing shrubs, were particularly attractive and became known as “kakapo gardens.”

Today, all kakapo occupy predator-free sanctuaries selected for their natural vegetation, shelter, and absence of invasive mammals. On Whenua Hou and Anchor Island, birds live in rimu-rata forests, where periodic rimu mast-fruiting events act as breeding cues. On Maud Island and Hauturu, kakapo have been observed selecting for five-finger treeland and even pine plantations in certain seasons, while actively avoiding dense manuka and open pasture.

A new trial site at Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari, located on New Zealand’s mainland, offers a reconstructed forest ecosystem behind one of the world’s longest pest-proof fences. Though only male birds are currently present, this site may offer a model for future reintroductions.

As the population grows, habitat expansion remains a pressing goal. Long-term plans include returning kakapo to large-scale, predator-free landscapes such as Stewart Island/Rakiura, contingent on the success of national eradication initiatives like Predator Free 2050.

Behavior

The kakapo is a nocturnal and ground-dwelling species, typically active during the night and roosting under vegetation or in tree hollows during the day. Despite being flightless, kakapo are agile movers: they walk with a distinctive “jog-like” gait, and are capable of traveling several kilometers in a single night. During the breeding season, males may walk up to 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) to reach their mating arenas, while nesting females have been observed making repeated foraging trips of over 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) from the nest.

Though they cannot fly, kakapo are excellent climbers. Using their strong, clawed feet, they ascend trees to forage or seek shelter, and may climb over 20 meters (66 feet) into the canopy. When descending, they sometimes leap from branches and use their wings to control their fall, gliding short distances of 3-4 meters (10-13 feet) – a behavior described as “parachuting.”

Their locomotion and energy use are efficient; with a low percentage of body mass allocated to flight muscles, kakapo have reduced metabolic demands and can thrive on lower-quality food sources. Home range size varies by age, sex, and season but tends to remain stable over years in both adult males and females.

Social structure and interactions

The kakapo has long been considered a solitary species, with males and females typically interacting only during the breeding season. However, recent observations challenge the extent of this isolation. Females and juveniles are occasionally seen in loose associations of two to four birds, sharing trees or foraging spaces. Subadult males have also been found roosting near older males during lekking periods, and individuals may maintain low-frequency contact using vocalizations such as the loud skraak.

Young kakapo are known to engage in social play, though less intensely and less reciprocally than their more social relatives, the kea and kaka. Play behavior often involves mock wrestling, with one bird hooking its neck under another’s chin, and is most frequent among juveniles.

While social interaction is limited, kakapo display high individual variation in personality, ranging from shy to curious, playful, or food-obsessed. Hand-reared birds, particularly those imprinted on humans, can become highly interactive and show clear responses to familiar people, suggesting a capacity for individual social learning despite the species’ solitary lifestyle.

Sensory and defensive adaptations

Despite their bulk and limited mobility, kakapo are highly sensory birds, possessing adaptations that reflect both their nocturnal habits and historic predator landscape. They have a well-developed sense of smell, unusual among parrots, which aids in locating food in the dark and may also be used in navigation. Their hearing is acute, and their vision is adapted to low light, with retinal features optimized for twilight activity. However, this comes at the cost of poor visual acuity, particularly in daylight.

Kakapo rely on cryptic plumage and stillness as their primary defenses. When threatened, they often freeze in place, blending seamlessly into their surroundings – a strategy that was highly effective against extinct visual predators such as Haast’s eagle and Eyles’ harrier. This behavior, however, offers little protection against mammalian predators, which hunt primarily by scent and sound. The species’ natural musty-sweet odor, while perhaps aiding social recognition, makes them especially vulnerable to detection by introduced mammals like stoats and cats.

While kakapo were once well-adapted to New Zealand’s pre-human ecosystem, their survival today depends on a network of human caregivers. Conservationists have developed close relationships with many individuals, and the species’ ongoing recovery is a testament to its adaptability, resilience, and surprising behavioral complexity in a world that has changed dramatically around it.

Breeding

The kakapo has one of the most unusual reproductive strategies among birds. It is the only flightless bird, and the only parrot, known to exhibit lek breeding behavior, where males gather to perform acoustic and physical displays in fixed locations (known as leks) to attract females.

Breeding is highly infrequent, occurring only in years of mast fruiting, particularly when rimu trees produce large seed crops, which happens every two to five years. Kakapo are slow to mature: males typically begin displaying at five years old, while females may breed from as early as five but more commonly at eight to nine years of age. The lack of annual breeding, combined with a long lifespan and low reproductive output, contributes to the species’ extremely slow population growth.

Mate selection and courtship

In breeding years, adult males abandon their usual home ranges and travel to elevated sites such as ridges, hilltops, or rocky clearings to establish track-and-bowl courts. These leks are spaced an average of 50 meters (164 feet) apart and can be located up to 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) from the male’s usual territory. Each court is composed of shallow, saucer-shaped depressions, or bowls, dug into the ground, connected by a network of cleared tracks. Bowls are often placed near natural acoustic reflectors like boulders or tree trunks to project sound more effectively.

From these bowls, males emit long sequences of deep, low-frequency booms (below 100 Hz) produced by inflating a thoracic air sac. These calls can travel up to 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) on still nights. After 20-30 booms, the male adds a high-pitched ching to help pinpoint his location. A single male may call for 6-8 hours per night, every night for up to four months, potentially producing tens of thousands of vocalizations and losing a significant portion of his body weight in the process.

Females are drawn by the booming and may walk several kilometers to reach a chosen male. Upon arrival, the male performs a visual and auditory courtship display, rocking side to side, clicking his beak, and walking backward toward the female with spread wings. Mating may last 40 minutes or more, after which the female departs to nest and raise chicks alone. No pair bond is formed, and males take no part in chick rearing.

Nesting, incubation, and hatching

The female constructs her nest on the ground, typically in a natural depression, under dense vegetation, or inside tree hollows, caves, or among roots. She lays 1 to 4 eggs, several days apart. The nest site is carefully selected for shelter and concealment, and may be reused in future breeding years. Once the first egg is laid, incubation begins immediately.

Incubation lasts approximately 30 days, during which the female must leave the nest unattended each night to forage. This exposes the eggs to cold stress and, historically, to predation. During this period, the female is entirely responsible for maintaining the eggs and ensuring adequate nutrition for herself.

Chicks hatch covered in grey down and are fully altricial, requiring constant care. The female feeds her chicks for about three months, with extended support continuing sporadically for up to six months after fledging. Chicks begin to leave the nest at 10 to 12 weeks, but remain dependent for some time.

Reproductive development and offspring dynamics

Sexual development and environmental conditions influence not just breeding timing but also offspring sex ratio. Well-nourished females are more likely to produce male offspring, who are larger and require more resources, but can potentially mate with multiple females. This phenomenon, consistent with the Trivers-Willard hypothesis, has implications for captive management: nutrient-rich diets may skew sex ratios toward males, complicating long-term recovery goals.

Kakapo breeding is tightly linked to ecosystem cycles and is among the most energetically demanding and behaviorally complex reproductive systems known in birds. Its irregularity and female-only parental care make successful breeding events particularly valuable to species conservation.

Lifespan

The kakapo holds the distinction of being the longest-living bird species known to science. While average life expectancy is estimated at around 60 years, individual birds may live considerably longer. The most famous example is Richard Henry, a male kakapo captured in Fiordland in 1975. Thought to be an adult at the time, he lived in captivity until 2010, making him approximately 80 years old at the time of his death. Some experts believe that under ideal conditions, kakapo may approach or exceed 100 years.

This remarkable longevity is linked to the kakapo’s slow life history strategy, characterized by delayed sexual maturity, low reproductive frequency, and long parental investment. Males begin lekking behavior at around five years of age, and females may not breed until they are five to nine years old. Even then, successful breeding is restricted to mast years, which occur unpredictably every two to five years depending on the forest type.

Despite their long potential lifespan, kakapo face a number of mortality risks, many of which stem from their evolutionary naivety to mammalian predators. Historically, adult birds were killed by introduced species such as cats and stoats, particularly during the breeding season when booming males were most conspicuous. Nesting females and chicks were especially vulnerable when left unprotected at night.

Even in predator-free sanctuaries, mortality may result from accidental injury, illness, or reproductive complications, such as egg-binding or crushed eggs in poorly constructed nests. Chicks are also susceptible to infection, developmental issues, or malnutrition, particularly when food availability does not match breeding effort in a mast year.

Human intervention has greatly reduced preventable mortality through nest monitoring, veterinary care, and individual management plans, but kakapo remain at risk due to their fragile reproductive biology and limited genetic diversity. These factors continue to pose challenges for long-term population viability, despite the species’ extraordinary lifespan.

Diet

The kakapo is an entirely herbivorous bird with a specialized diet adapted to its low-energy lifestyle and unique digestive anatomy. Its beak is designed for grinding plant matter with precision, allowing it to extract nutrients from tough foliage, fibrous bark, rhizomes, and roots.

Instead of a large muscular gizzard like many birds, the kakapo has a reduced gizzard and likely relies on foregut fermentation aided by symbiotic bacteria. It feeds on a wide variety of native plants, including ferns, mosses, fruits, seeds, tubers, and flowers, with over 60 genera identified in coprolite studies.

One distinctive feature of kakapo feeding is the production of fibrous “chews” – small balls of indigestible plant matter left hanging from browsed vegetation after the bird has extracted the soft, nutrient-rich tissues.

Kakapo foraging behavior is flexible and opportunistic, shifting with the seasons and availability of key plant species. Individual birds maintain feeding areas ranging from 100 to 5,000 square meters (1,000-54,000 square feet), often leaving signs such as numerous droppings or stripped vegetation.

Among the most critical dietary components is the fruit of the rimu tree (Dacrydium cupressinum), which is consumed almost exclusively during mast years and plays a pivotal role in triggering breeding. Nutrient analysis of rimu fruit shows it is high in carbohydrates, fatty acids, calcium, and vitamin D, making it particularly suited for egg formation and chick development.

During poor fruiting years, conservationists provide supplementary feeding using nutritionally tailored pellets to support reproduction and chick survival. However, natural foods like rimu berries appear to deliver a unique nutritional profile that artificial diets cannot fully replicate, underscoring their importance in kakapo ecology and breeding success.

Culture

The kakapo holds deep significance in Maori culture, where it is remembered not only as a source of food and materials but also as a bird of mystery and symbolic power. Traditionally regarded as a taonga (treasured) species, the kakapo was associated with foresight and natural rhythms. Its irregular breeding cycle, tied to the heavy fruiting (masting) of native trees like rimu, led Maori to believe the bird could predict the future.

According to oral tradition, kakapo were observed dropping seasonal berries such as hinau and tawa into pools of water to preserve them. This behavior became the basis for a food storage practice adopted by Maori communities, further cementing the bird’s reputation as a wise and resourceful forest inhabitant.

Maori folklore also offers a mythic origin for the kakapo’s life in the forest. One story tells of a time when the kakapo and the albatross (toroa) swapped domains – albatross taking to the ocean skies while the kakapo retreated to the shadowed forests of Aotearoa. With its moss-green plumage and silent nocturnal habits, the kakapo vanished into the deep bush, safe from predators until the arrival of humans.

Despite being widely hunted, the bird was treated with reverence. Its feathers were painstakingly woven into cloaks and capes (kahu kakapo), garments so valued for their warmth and beauty that a popular saying warned against ingratitude: “You have a kakapo cape and you still complain of the cold.” Only one fully intact kakapo-feather cloak is known to survive today.

The bird’s courtship behavior also became embedded in traditional knowledge. During the breeding season, males gathered in ground bowls (whawharua) and performed booming rituals, sometimes observed by hunters who noted the presence of a smaller sentinel bird – the tiaka, that circled the edge of the arena. If the tiaka was caught first, the rest of the flock could be captured more easily. This deep familiarity with kakapo behavior informed hunting practices for generations.

The bird was also kept as a companion animal, with early European settlers noting its affectionate and dog-like demeanor. As both a cultural icon and a living link to pre-human Aotearoa, the kakapo remains one of New Zealand’s most emblematic and storied birds.

Threats and conservation

Once widespread across New Zealand, the kakapo is now confined to a handful of offshore islands and remains one of the world’s most intensively managed bird species – and among the rarest surviving parrots worldwide. As of 2025, only 242 individuals are known to exist, and the species is classified as Critically Endangered.

Despite decades of conservation work, its long generation time, low natural fertility, and persistent ecological vulnerabilities make recovery an ongoing challenge. The Kakapo Recovery Programme, established in 1995, continues to play a vital role in increasing population size and safeguarding the future of the species.

Threats

The kakapo’s decline began with the arrival of the Maori, who hunted the bird for meat and feathers. Introduced predators, such as Polynesian rats and dogs, further reduced numbers, especially due to the kakapo’s flightlessness and tendency to freeze when threatened. Widespread habitat destruction followed European colonization, and the introduction of stoats, cats, and black rats greatly accelerated the species’ decline. By the 1970s, only a few individuals remained, all of them males, and extinction appeared imminent.

Even after rediscovery on Stewart Island in 1977, the population faced rapid losses: feral cats were killing more than 50% of monitored birds annually. Subsequent threats included disease outbreaks such as cloacitis and aspergillosis, infertility, and a strongly male-skewed sex ratio. Competition with introduced herbivores and low genetic diversity further limited recovery prospects. Browsing by possums and deer also degraded native forests, reducing the availability of key food sources.

Although predator-free islands were eventually secured, kakapo still require intensive management, including nest monitoring, disease screening, and close tracking of every individual.

Conservation efforts

The rescue of the kakapo is one of the most remarkable conservation stories in avian history. Beginning with emergency translocations in the 1980s, the population was gradually moved to predator-free islands such as Whenua Hou and Anchor Island. Supplementary feeding and active nest management dramatically improved breeding success. From just 51 individuals in 1995, the population rose steadily to over 240 by 2025, with record breeding seasons in 2016 and 2019 due to rimu mast events and artificial insemination efforts.

All surviving kakapo are radio-tagged and named, with their movements, health, and reproductive activity monitored year-round. Eggs are often removed for artificial incubation, and chicks are sometimes fostered or hand-reared. Genetic research, including genome sequencing of all living birds, has helped reduce inbreeding and improve fertility rates.

In 2023, the species returned to mainland New Zealand for the first time in nearly 40 years, with the reintroduction of birds to Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari. Although some escaped the enclosure, the event marked a new phase in recovery planning.

The current goal of the Kakapo Recovery Programme is to establish at least one self-sustaining wild population. Resolution Island is being prepared for this purpose, while researchers continue to model future release sites.

Despite ongoing disease threats and habitat constraints, the coordinated conservation strategy, combining field management, ecological restoration, public engagement, and advanced biotechnology, offers hope for the long-term survival of this unique nocturnal parrot.

Future outlook

The future of the kakapo remains delicately balanced between remarkable recovery and persistent vulnerability. After teetering on the edge of extinction with just 51 birds in the 1990s, the species has made steady gains through a globally recognized conservation program that combines traditional ecological knowledge, advanced genetics, and intensive field management. With a current population of 242 individuals, the kakapo’s survival now depends not only on continued human intervention but on the ability to scale solutions for long-term resilience.

Key priorities in the years ahead include the establishment of a self-sustaining wild population, expansion into new predator-free habitats, and preservation of genetic diversity in the face of extreme inbreeding. Technological innovations, from genome sequencing to remote nest monitoring, offer powerful tools, but recovery efforts must remain adaptive in the face of disease risks, climate variability, and habitat limitations. The recent reintroduction to mainland New Zealand marks a significant milestone, but also underscores the challenges of coexistence in human-dominated landscapes.

As both a symbol of vulnerability and a testament to what dedicated conservation can achieve, the kakapo occupies a singular place in New Zealand’s natural heritage. Its story is not yet complete, but with sustained commitment, scientific innovation, and cultural stewardship, the world’s last flightless, nocturnal parrot may yet reclaim a secure future in its native forests.

Further reading