The great tit (Parus major) is one of the most widespread and recognizable songbirds of the Palearctic region, ranging across Europe, North Africa, and much of Asia. A member of the Paridae family, it is known for its bold black-and-yellow plumage, distinctive head markings, and varied, melodious song. Highly adaptable and intelligent, the great tit thrives in a wide range of habitats, from dense forests to urban gardens. Its curiosity and problem-solving abilities make it a frequent subject of behavioral studies, while its loud, clear calls contribute to the vibrant soundscape of its surroundings.

| Common name | Great tit |

| Scientific name | Parus major |

| Order | Passeriformes |

| Family | Paridae |

| Genus | Parus |

| Discovery | First documented by F. Willughby in the 17th century, described by C. Linnaeus in 1758 |

| Identification | Medium-sized songbird with a black head, white cheek patches, bright yellow underparts with a black central stripe, and olive-green upperparts |

| Range | Widespread across Europe, North Africa, and temperate to subtropical Asia |

| Migration | Mostly resident, but some northern and eastern populations migrate irregularly in response to food shortages |

| Habitat | Found in deciduous and mixed forests, woodland edges, parks, gardens, and urban areas |

| Behavior | Active, intelligent, and highly adaptable; forms hierarchical flocks in winter; known for problem-solving skills and cultural transmission of learned behaviors |

| Lifespan | Typically 2-3 years in the wild, but some individuals have lived up to 15 years |

| Diet | Primarily insects and other invertebrates during breeding season; switches to seeds, fruits, and human-provided food in winter |

| Conservation status | Least Concern (IUCN); stable global population, but habitat loss and climate change may impact localized populations |

| Population | Estimated 440-695 million mature individuals globally; Europe holds the largest share with 130-210 million mature individuals |

Discovery

The great tit has been known to European naturalists for centuries, with early descriptions appearing in ornithological texts before formal taxonomy was established. Francis Willughby, a 17th-century English naturalist, documented the species in his writings, but it was Carl Linnaeus who provided its first formal scientific description in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae in 1758. Linnaeus classified it under its current binomial name, Parus major, a designation that has remained unchanged. The name derives from Latin, with parus meaning “tit” and maior referring to its relatively large size compared to other members of the Paridae family.

Historically, the great tit was considered a widespread species ranging from Europe to Japan and south into Indonesia. Earlier classifications included 36 described subspecies, traditionally grouped into four main lineages: major, minor, cinereus, and bokharensis. The major group contained populations across Europe, North Africa, and northern Asia. The minor group occupied southeastern Russia, Japan, and parts of northern Southeast Asia. The cinereus group was distributed from Iran across South Asia to Indonesia, while the bokharensis group included three subspecies found in Central Asia. For a time, some taxonomists treated Parus bokharensis, also known as the Turkestan tit, as a separate species, and early hypotheses suggested that the great tit formed a ring species around the Tibetan Plateau, with genetic exchange between the subspecies.

Molecular studies in the early 2000s challenged this classification. A 2005 study analyzing mitochondrial DNA sequences demonstrated that the major group was distinct from the minor and cinereus groups and that the bokharensis lineage had diverged from the major group approximately 500,000 years ago. Genetic evidence revealed that the minor and cinereus groups had been reproductively isolated long enough to be considered separate species, leading to the reclassification of the cinereous tit (Parus cinereus) and the Japanese tit (Parus minor). However, some recent taxonomies no longer recognize Parus minor as a distinct species, instead considering it a part of Parus cinereus. The bokharensis group, however, was found to be too closely related to the great tit to warrant species status and was merged back into Parus major. This taxonomic revision has been adopted by authorities such as the IOC World Bird List, while other classifications, including those in Handbook of the Birds of the World, retain a more traditional approach by keeping Parus minor and Parus cinereus within the great tit complex.

The dominance of the Parus major major subspecies across a vast range suggests that it underwent a rapid post-glacial expansion. Genetic studies support the theory that the nominate subspecies recolonized much of Europe and Asia after the last ice age, likely from a single glacial refuge in the Mediterranean region. Evidence of a genetic bottleneck, followed by a population expansion, further supports this hypothesis. Unlike some other members of Paridae, the great tit does not engage in food-hoarding behavior, a characteristic that has been used in morphological and genetic studies to define evolutionary relationships within the family. Although the genus Parus originally contained most of the world’s tit species, taxonomic revisions in 1998 led to its subdivision, with some species being moved to genera such as Cyanistes. The great tit remains within Parus, but further genetic research may result in additional refinements to its classification.

Despite its widespread presence and adaptability, the great tit exhibits genetic continuity across much of its range. Hybridization with closely related species, including the Eurasian blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus), coal tit (Periparus ater), and possibly the marsh tit (Poecile palustris), has been recorded but remains rare. The evolutionary and taxonomic history of Parus major continues to be an active area of research, particularly concerning subspecies relationships and regional genetic variation.

Identification

The great tit is a medium-sized passerine bird, recognized for its bold coloration and distinctive markings. It is the largest species of tit in its range, measuring between 12.5 and 15 centimeters (4.9 to 5.9 inches) in length, with a wingspan of 22 to 25 centimeters (8.7 to 9.8 inches), and a weight ranging from 15 to 22 grams (0.53 to 0.78 ounces). Individuals from colder northern regions tend to be slightly larger and heavier than those from milder climates, a common pattern in birds following Bergmann’s rule.

The species displays sexual dimorphism, with males typically having more pronounced markings than females. Adult great tits have a black head and throat, with bright white cheek patches that contrast sharply with their dark crown. Their underparts are yellow, divided by a central black stripe that varies in width among individuals and subspecies. The upperparts are olive-green, and the wings have a bluish tinge with a distinct white wing bar. The tail is mostly black with white outer feathers. Males generally have a broader and more defined black chest stripe, whereas in females, the stripe is narrower and may appear broken or faded. The black coloration of the head and throat in males is also glossier, while females tend to have a slightly duller tone.

Juveniles and immature great tits differ from adults in several ways. Their yellow underparts are paler, and their cheek patches are buff-colored rather than pure white. The black head and throat markings are less distinct, and the central black stripe on the belly is narrower and less defined. After their first summer, young birds molt into adult-like plumage, though some individuals may retain traces of their juvenile features into their first winter.

Variation in plumage coloration

While the typical plumage of the great tit is well recognized, studies have shown that its yellow breast color varies depending on environmental conditions, season, and diet. Research conducted in Norway found that nestlings raised in deciduous forests have more intensely yellow plumage than those raised in coniferous forests, likely due to differences in available food sources. Additionally, birds raised later in the breeding season tend to be more yellow than those fledging earlier. Experimental studies confirmed that diet, particularly the consumption of lepidopteran larvae such as green caterpillars, plays a crucial role in determining plumage coloration rather than genetic differences alone.

Recent research has also linked climate conditions during molt to variations in plumage coloration. A study in Hungary found that great tits molting in warmer, drier conditions developed darker and more saturated yellow feathers, whereas birds that molted in cooler, wetter conditions exhibited paler and less intense yellow plumage with higher ultraviolet reflectance. These findings suggest that environmental factors, including food availability and climatic conditions, influence the expression of carotenoid-based coloration in the species. Such variation may have implications for communication, sexual selection, and potential adaptation to changing climates.

Vocalization

The great tit is a highly vocal species with a diverse repertoire of calls and songs used in communication. Males sing prominently during the breeding season, producing repeated, rhythmic phrases that vary in pitch and structure. The most common song pattern consists of a simple, two- or three-note phrase repeated multiple times. Great tits are also known for their high intelligence and adaptability, which extends to their vocal abilities. While not true vocal mimics like some other passerines, they can modify their calls in response to environmental and social cues, demonstrating an impressive capacity for learning and adjusting their vocalizations based on context.

Listen to the great tit call:

Studies have shown that great tits engage in song matching, a behavior where individuals respond to a rival’s song by repeating the same song type. This is often observed in territorial disputes, where song matching can signal aggression or dominance. Birds are more likely to match songs that closely resemble their own, suggesting that song learning and recognition play a role in their social interactions. Research on song transmission in deciduous forests has also revealed that foliage density affects how sound travels, with songs becoming more degraded after leaf emergence. This means that great tits may adjust their singing position or song structure to maintain effective communication.

Beyond singing, great tits use a variety of calls for alarm, social interaction, and mate communication. Their mobbing calls, used to alert others to predators, are particularly sophisticated. Studies have shown that great tits modify their mobbing calls based on the perceived threat level of a predator. When confronted with a high-risk predator such as a sparrowhawk, they produce longer and more frequent calls compared to those given in response to a lower-threat predator like a tawny owl. The number of calls also increases in larger flocks, suggesting that social context influences mobbing behavior.

Vocal communication between mates also plays a role in great tit behavior. During the dawn chorus, males sing intensely near the nest, particularly before and during egg laying. In response, females produce a unique “quiet call” from inside the nest box – a low-amplitude sound audible only at close range. This previously undocumented vocalization suggests that mate communication during breeding is more interactive than previously thought. The ability of great tits to modify their vocal signals based on context, social dynamics, and environmental factors highlights their advanced cognitive abilities and the complexity of their communication system.

Range

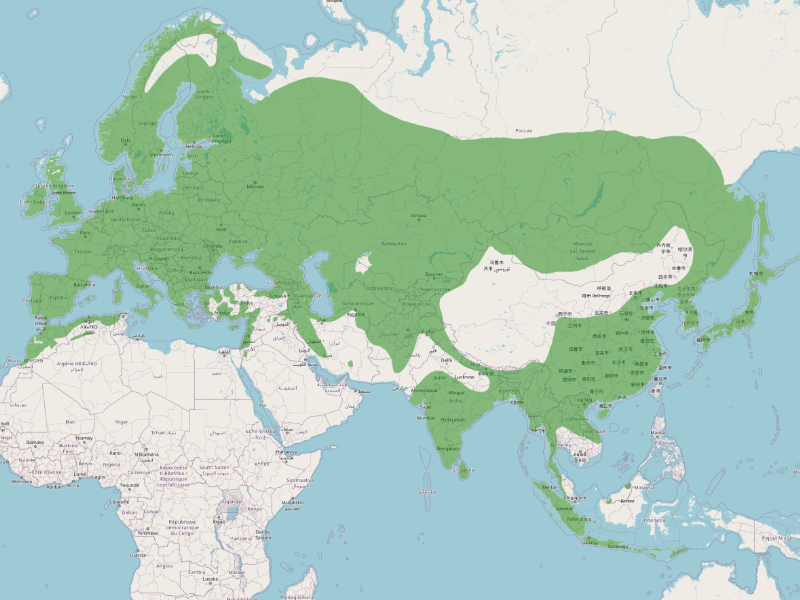

The great tit has one of the most extensive distributions of any passerine bird, covering much of Europe, North Africa, and Asia. It is found from the Atlantic coasts of Portugal and the British Isles in the west to Japan and eastern Russia in the east. Its range extends from the northern boreal forests of Scandinavia and Siberia to the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and parts of Central and South Asia. The species is highly adaptable, occupying a wide variety of habitats, including deciduous and mixed forests, urban parks, gardens, and agricultural landscapes.

Historically, the range of the great tit has expanded and shifted due to climatic changes and habitat modifications. Genetic studies suggest that during the last ice age, the species was confined to glacial refugia in southern Europe and parts of Asia. As the glaciers retreated, it recolonized northern and central Europe, leading to the dominance of the nominate subspecies (Parus major major) across much of its range. In contrast, more isolated populations in Asia and the Middle East evolved into distinct subspecies, some of which were formerly classified as separate species.

The distribution of subspecies within Parus major varies across its vast range. The nominate subspecies (P. m. major) is the most widespread, occurring from western Europe to western Siberia. The bokharensis group, which includes the Turkestan tit (P. m. bokharensis), inhabits Central Asia and is adapted to drier environments. The minor group is distributed across eastern Asia, including China, Korea, and Japan, while the cinereus group, often considered a separate species (Parus cinereus), is found in South and Southeast Asia, from India to Indonesia. Some subspecies are restricted to islands, such as P. m. corsus in Corsica.

The overall distribution of the great tit is largely stable, and the species has even benefited from urbanization in some regions. However, in parts of its range, habitat fragmentation and climate change may influence local populations. Conservation efforts generally focus on habitat preservation and ensuring suitable breeding conditions, particularly in regions where specific subspecies are more vulnerable to environmental changes.

Migration

The great tit is largely a resident species across much of its range, with birds in southern and central Europe, North Africa, and temperate Asia remaining in their breeding territories year-round. However, populations in northern and eastern Europe, as well as parts of Siberia, display partial migration, with some individuals moving south in autumn. These movements vary depending on local conditions, and while great tits are sometimes observed migrating in large numbers, studies indicate that they do not follow the patterns of true irruptive migrants.

Research based on ringing data from the Baltic region shows that great tits behave more like regular partial migrants rather than irruptive species. Unlike species such as the coal tit (Parus ater) or great spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos major), whose migration numbers fluctuate dramatically between years, great tit migration is relatively stable. While the number of migrating individuals varies across different locations, their movements are not strongly influenced by winter food availability, such as fluctuations in beechnut crops. The species’ migratory behavior appears to be more consistent and less dependent on external food resources than that of classic irruptive migrants.

In addition to partial migration, some great tits engage in altitudinal migration, moving from higher elevations to lower valleys outside the breeding season. This behavior is observed in populations inhabiting mountainous regions, where winter conditions at higher altitudes make food less accessible. Despite these seasonal movements, most great tits remain within relatively short distances of their breeding grounds.

Recent studies suggest that climate change may be influencing great tit migration patterns. Warmer temperatures have led to earlier breeding seasons in parts of Europe, potentially altering dispersal dynamics. While some populations remain genetically adapted to migration, others may be shifting toward increased residency in response to changing environmental conditions. These variations highlight the species’ adaptability and the complex factors that shape its movement patterns across different regions.

Habitat

The great tit is highly adaptable and occupies a wide range of habitats across its vast distribution. It primarily inhabits deciduous and mixed woodlands, favoring areas with a dense tree canopy and abundant undergrowth. While it is commonly associated with oak, beech, and other broad-leaved forests, it can also be found in coniferous woodlands, particularly at the northern edges of its range. The species is present from lowland forests to mountainous regions, occurring at elevations up to 2000 meters (6560 feet) in some parts of its range, with altitudinal migrations observed in populations from higher elevations.

Despite its strong association with natural woodlands, the great tit thrives in human-modified environments and is frequently seen in urban parks, gardens, orchards, and farmland. It is one of the most successful passerines in adapting to suburban and city landscapes, readily taking advantage of artificial nest sites, including bird boxes and building crevices. In agricultural areas, it can be found along hedgerows, orchards, and wooded edges, where it benefits from a mix of trees and open spaces.

The habitat preferences of great tit subspecies vary across different regions. In Europe and northern Asia, the nominate subspecies (P. m. major) is most common in temperate broadleaf and mixed forests. The bokharensis group, found in Central Asia, inhabits drier woodlands, including riparian forests and semi-arid landscapes. In South Asia and Southeast Asia, the cinereus group prefers tropical forests, where it can be found in dense foliage and bamboo thickets. Some insular subspecies, such as those in Corsica or Japan, have adapted to specific local habitats, often with minor variations in foraging behavior and nesting preferences.

Behavior

The great tit is an active and highly adaptable bird with complex social structures and a wide range of behaviors. It is primarily diurnal, spending much of the day foraging, interacting with conspecifics, and defending territories. While pairs dominate during the breeding season, great tits join mixed-species flocks in autumn and winter, forming hierarchical social structures where dominance influences access to resources. Males generally maintain their territories year-round, while younger or lower-ranking individuals often disperse to find less contested areas.

Great tits exhibit stable personality traits, with individuals consistently displaying either bold, exploratory behavior or more cautious, reactive tendencies. Studies show that fast-exploring birds are typically more aggressive and take less time to attack in conflicts, whereas slow explorers are more hesitant but exhibit greater behavioral flexibility. In urban environments, where competition is higher, great tits tend to be more aggressive than their rural counterparts, showing increased territorial defense and adaptability to human-altered landscapes.

Cognitive abilities play a significant role in great tit behavior, influencing problem-solving skills and decision-making. Research has demonstrated that great tits have a higher degree of self-control than most small passerines, with performance in cognitive tests comparable to some corvids. This ability allows them to adapt to complex challenges in their environment, including learning to access novel food sources. Their intelligence is also evident in observational learning, as seen in historical cases where great tits learned to pierce milk bottle caps to reach cream, a behavior that spread culturally across populations. These cognitive abilities place great tits among the most intelligent songbirds, ranking them among the notable examples of avian intelligence, where they stand alongside problem-solving specialists such as corvids and parrots.

During winter, dominance relationships influence flock structure, with aggressive interactions more frequent among unfamiliar individuals. Badge size (the width of the black stripe on the chest) acts as a status signal in initial encounters, with birds displaying larger badges more likely to dominate strangers. However, among familiar individuals, motivation and experience override badge size, showing that dominance is influenced by both physical traits and learned behaviors.

Breeding

The great tit is a socially monogamous species that establishes breeding territories as early as late January, with territory defense intensifying in late winter and early spring. These territories are typically reoccupied in successive years, provided the previous brood was successfully raised. However, if a nest is predated, the female is more likely to disperse and establish a new territory elsewhere.

Pair bonds usually last for a single breeding season, though some pairs remain together for multiple years. Although socially monogamous, extra-pair copulations are frequent, with studies showing that up to 40% of nests contain offspring fathered by males other than the social partner, and around 8.5% of all chicks result from cuckoldry. Older males generally have higher reproductive success than sub-adult males, likely due to greater territorial dominance and experience.

Breeding occurs seasonally, with timing dependent on location, temperature, and food availability. Most great tits begin breeding in March or April, though populations in warmer regions may start as early as January, while in northern latitudes, egg-laying is delayed until May. Exceptionally, breeding has been recorded in Israel between October and December. A strong correlation exists between laying date and peak caterpillar abundance, meaning females time egg-laying to match food availability for their nestlings. Older females tend to lay earlier than younger females.

Nesting and clutch size

Great tits are cavity nesters, selecting tree holes, rock crevices, or walls as nesting sites, but they readily adapt to nest boxes. The female alone constructs the nest, using moss, grass, plant fibers, wool, hair, and feathers for insulation. Clutch size varies from 5 to 12 eggs, though extremes of 3 to 18 eggs have been recorded. Clutch size tends to decrease with later laying dates and is influenced by competition density, with smaller clutches in areas of high population density. Insular populations, such as those on offshore islands, generally lay smaller clutches but larger eggs compared to mainland birds.

The eggs are white with red speckles and are incubated exclusively by the female for 12 to 15 days, during which the male provides food. The female sits closely on the eggs and may hiss defensively when disturbed. Environmental conditions after laying can affect hatching synchronization, with females sometimes delaying incubation or adding extra eggs if food availability changes.

Chick development and parental care

Hatchlings are blind, featherless, and entirely dependent on parental care. Unlike most altricial birds, which have dun-colored nestlings, great tit chicks develop plumage with carotenoid-based yellow coloration, similar to adults. Their yellow nape patch reflects ultraviolet light, likely functioning as a signal to attract parental attention and possibly indicating chick fitness. This patch fades after the first molt at around two months old and continues to shrink as the bird matures.

Both parents actively feed the chicks and maintain nest hygiene, removing fecal sacs to keep the nest clean. Chicks receive 6 to 7 grams (0.21 to 0.25 ounces) of food daily, consisting mostly of caterpillars and insects. The nestling period lasts 16 to 22 days, after which the chicks fledge but remain partially dependent on their parents. Parental feeding continues for up to 25 days in first broods, but for as long as 50 days in second broods. Chicks from second broods tend to have weaker immune systems and poorer body condition, leading to lower juvenile survival rates.

Post-fledging survival is also influenced by territorial competition and inbreeding avoidance mechanisms. Dispersal from the birthplace reduces the risk of inbreeding, as inbred offspring exhibit lower fitness due to increased expression of deleterious alleles. This natural tendency toward dispersal ensures genetic diversity in great tit populations.

Environmental and human influences on breeding

Environmental conditions strongly impact reproductive success, particularly in urban versus rural populations. Urban great tits generally lay smaller clutches, earlier in the season, and experience lower fledging success, primarily due to reduced food availability. Studies show that urban chicks are lighter, have duller yellow plumage, and grow more slowly compared to their rural counterparts. In contrast, forest populations, while facing higher predation risks, benefit from greater food abundance and produce larger clutches with healthier chicks.

Pollution also affects breeding success. Studies near industrial sites with heavy metal pollution show reduced hatching and fledging rates, even when clutch size and incubation duration remain unchanged. Additionally, egg size is highly heritable (around 80%), but tends to decrease seasonally in urban populations, likely due to nutritional constraints affecting later breeders.

Despite these challenges, the great tit remains a highly adaptable breeder, successfully raising young in natural forests, suburban gardens, and even highly urbanized areas. However, ongoing habitat changes, food availability, and pollution continue to shape the species’ reproductive strategies across its range.

Lifespan

Great tits typically live 2 to 3 years in the wild, though individuals that survive their first year can live much longer. The oldest recorded great tit reached 15 years, but such longevity is rare.

Survival rates vary significantly depending on age, sex, habitat, and environmental factors. Juvenile mortality is high, with only 15-22% of fledglings surviving to their first breeding season. Those that do survive their first year have an annual survival rate of 30-60%, with males generally outliving females. Harsh winters are one of the greatest threats, with up to 80% mortality in particularly severe years. Food availability also plays a critical role, particularly in northern populations, where survival is closely linked to beechnut abundance in winter.

Male great tits tend to have higher survival rates than females, possibly due to their dominance in territory defense and greater access to resources. Females, especially during the breeding season, experience higher energy demands and may abandon broods under extreme stress to increase their own survival chances. Competition with other species, particularly blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus), reduces male survival, likely due to increased territorial conflicts.

Urban and rural populations show different survival patterns. Urban great tits tend to have lower breeding success but higher winter survival, benefiting from warmer temperatures and supplemental food sources provided by humans. However, urban nestlings often develop more slowly and in poorer condition, which may impact long-term survival.

Despite high mortality rates, great tits remain a resilient species, capable of adapting to diverse environments, from dense forests to city parks. Most individuals live only a few years, but those that navigate early-life challenges can persist for nearly a decade or more.

Diet

The great tit is an opportunistic insectivore that adapts its diet based on seasonal availability of prey. While primarily feeding on insects and other invertebrates, it also consumes seeds and fruit, particularly in winter when animal prey is scarce.

During the breeding season, caterpillars and spiders form the bulk of the diet, particularly for nestlings. Studies show that spiders dominate early in the season, making up to 75% of prey biomass, before being largely replaced by caterpillars once they reach an optimal size of 10-12 milligrams. Caterpillars can account for 80-90% of the diet at peak availability. The switch from spiders to caterpillars occurs suddenly, suggesting that prey size, rather than just abundance, dictates preference.

Nestlings fed a higher proportion of caterpillars exhibit faster growth and better fledging success, while those in food-scarce years or habitats may receive more spiders as compensation, though with reduced growth rates. Other arthropods, such as beetles and orthopterans, are occasionally consumed but appear to be less optimal for chick development.

Outside the breeding season, great tits become more generalist, expanding their diet to include seeds, berries, and other plant material. In winter, they forage on tree bark, twigs, leaf litter, and even walls in search of dormant insects. They may also move closer to human settlements, feeding at bird tables, suet feeders, and kitchen scraps.

Foraging behavior

Great tits are highly adaptable foragers, adjusting their feeding height and location based on food availability. During winter, they primarily forage below 6-7 meters (20-23 feet), searching for insects in bark crevices and under leaves. In spring, their feeding height rises above 9 meters (30 feet), as they track caterpillar populations in the forest canopy.

They display selective foraging behavior, actively choosing high-quality prey rather than simply consuming the most abundant insects. Males tend to deliver more caterpillars, while females provide a higher proportion of spiders, suggesting sex-based differences in prey selection.

Great tits are also known for their behavioral flexibility and problem-solving abilities, which extend to food acquisition. They have been observed pecking open milk bottle caps to access cream, and in urban areas, they may scavenge novel food sources such as scraps and processed foods.

Digestive adaptations

Recent studies show that great tits have a highly flexible gut microbiome, allowing them to adjust to seasonal dietary changes. Their microbiota shifts based on whether they consume an insect-rich or seed-heavy diet, demonstrating a physiological adaptation that supports their survival across diverse environments.

In urban environments, great tits face nutritional challenges due to lower caterpillar availability, leading to reduced nestling growth and fledging success. However, they compensate by utilizing bird feeders and scavenging alternative food sources, which may improve winter survival but does not fully replace natural insect prey during breeding.

Culture

The great tit holds a special place in European and Asian culture, particularly as a symbol of adaptability, intelligence, and resilience. While not as deeply embedded in mythology as some birds, it has been referenced in folklore, literature, and scientific history, reflecting its close association with human settlements.

In Slavic and European traditions, the great tit is often considered a harbinger of winter, as it becomes more visible near homes and gardens when food in the wild becomes scarce. In Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, its arrival is sometimes seen as a sign that cold weather is approaching, and in some regions, feeding great tits in winter is thought to bring good luck. The bird’s active and inquisitive nature has also led to associations with curiosity and resourcefulness. This reputation was reinforced in the 20th century when great tits in the UK and parts of Europe were observed piercing milk bottle caps to access cream, an example of problem-solving and cultural learning that spread across populations.

The great tit has played a crucial role in behavioral and ecological research, becoming one of the most studied songbirds in the world. It has provided key insights into territoriality, vocal communication, mate selection, and climate adaptation, influencing modern ornithology and behavioral ecology. Long-term studies of great tit populations have helped scientists understand how birds respond to environmental change, making the species an important model in avian research. In literature and poetry, the great tit is often portrayed as a cheerful and energetic bird, brightening up gardens and woodlands, particularly in winter. It appears in British and Scandinavian nature writing, often described as a lively presence during the colder months. Its distinctive call and bold behavior make it a favorite subject for birdwatchers and wildlife enthusiasts.

Today, the great tit remains a familiar and well-loved garden bird throughout its range. It is commonly featured in conservation campaigns, educational programs, and citizen science initiatives. Its adaptability to urban environments has made it an important subject in climate change research, with its shifting breeding and migration patterns being closely monitored. Though not as steeped in myth as some other birds, the great tit’s cleverness, resilience, and close association with human environments have cemented its place in both scientific and cultural history.

Threats and conservation

The great tit is a widespread and abundant species, currently classified as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List. Its total European population is estimated at 130 to 210 million mature individuals, with 65 to 105 million breeding pairs. Europe represents approximately 30% of the species’ global range, leading to a rough global population estimate of 440 to 695 million mature individuals. While further validation is required, current data suggest that the global population has remained stable over at least three generations (approximately 10 years). Although the species has a medium dependency on forest habitat, ongoing deforestation is occurring at a slow rate within its mapped range.

Threats

Despite its adaptability, the great tit faces several natural and human-induced threats. Predation remains a major cause of mortality, particularly from birds of prey such as sparrowhawks (Accipiter nisus), as well as pine martens (Martes martes), snakes, and woodpeckers. Nestlings and fledglings are highly vulnerable, with many not surviving their first few weeks. To mitigate predation risks, great tits favor deep nesting cavities and adjust their foraging behavior, particularly in winter, by staying close to protective cover.

Seasonal food shortages, particularly in harsh winters, contribute to population fluctuations. The availability of beech mast and caterpillars plays a crucial role in survival, and years with low seed production often lead to increased mortality and dispersal. Habitat fragmentation exacerbates this issue by reducing access to both natural food sources and safe foraging locations.

Human-driven environmental changes present additional challenges. Deforestation and urbanization reduce the number of natural nesting cavities, leading to increased competition with other cavity-nesting birds such as blue tits. Pollution, particularly heavy metal contamination near industrial areas, has been linked to reduced reproductive success, with lower hatching and fledging rates.

Climate change is also influencing the species, particularly by disrupting the synchronization between breeding timing and peak caterpillar availability, which can negatively affect chick development. While great tits exhibit genetic adaptations to climate change, edge populations may struggle to keep pace with rapid environmental shifts, making them particularly vulnerable.

Conservation efforts

The great tit benefits from various conservation initiatives that help mitigate some of these threats. The species readily adapts to artificial nesting sites, and nest box programs have become an effective tool in areas where natural cavities are scarce. These programs are particularly beneficial in urban parks, managed forests, and suburban gardens, where competition for nesting sites is high.

Supplementary feeding also plays a key role in improving survival rates, especially in winter when natural food sources become scarce. Many great tits take advantage of bird feeders, suet blocks, and other artificial food sources, which have been linked to increased overwinter survival in human-dominated landscapes.

Long-term citizen science projects and ringing studies provide valuable data on population trends, migration patterns, and reproductive success. These monitoring efforts have helped confirm that great tit populations remain stable across their range, despite localized pressures from habitat loss and climate change. The species’ behavioral flexibility, diverse diet, and generalist foraging strategies make it one of the most resilient songbirds in Europe and Asia. However, ongoing habitat protection, pollution control, and climate adaptation measures will be essential in maintaining stable populations in the long term.

Similar species

The great tit (Parus major) is among the most recognizable small passerines in its range, but it can still be confused with several other tit species, particularly those within the Paridae family that share similar markings or distribution ranges. Regional variations in plumage and occasional hybridization events with closely related species can sometimes make identification more complex. However, key features such as size, color contrast, and chest markings help distinguish it from similar species.

Cinereous tit (Parus cinereus)

The cinereous tit, formerly considered a subspecies of the great tit, is now recognized as a separate species. It occurs across South and Southeast Asia, replacing the great tit in many regions. Unlike the great tit, the cinereous tit lacks yellow plumage, instead displaying a grayish-white underside with a black central stripe. Its overall appearance is more muted, and its call differs slightly, reflecting its distinct evolutionary history.

Turkestan tit (Parus bokharensis)

The Turkestan tit is another close relative, found in Central Asia, from Iran to western China. It is paler than the great tit, with a washed-out yellow underside or sometimes greyish-white underparts. This species prefers drier, more open woodland habitats compared to the great tit’s broader range, which includes forests, urban gardens, and mixed landscapes.

Eurasian blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus)

Among European species, the blue tit is sometimes mistaken for the great tit due to its similar size and behavior. However, it is significantly smaller and more slender, with a distinctive blue cap, white cheeks, and greenish-yellow body. Unlike the great tit’s bold black head, the blue tit’s face is brighter and lacks a strong black stripe down the chest.

Coal tit (Periparus ater)

The coal tit is another potential confusion species, especially in mixed forests where both species occur. It is noticeably smaller and more delicate, with a black cap and nape, but it lacks the great tit’s bright yellow belly and central black stripe. Instead, the coal tit has a whitish underside with a hint of buff or gray and a small white patch on the nape, distinguishing it from the larger, more robust great tit.

Future outlook

The great tit is more than just a common garden bird; it is a species that demonstrates remarkable intelligence, adaptability, and resilience. As one of the most studied birds in the world, it has provided key insights into avian behavior, learning, and climate adaptation. Its ability to solve problems, such as learning to open milk bottles, and its complex vocal communication and social dynamics place it among the world’s smartest bird species. At Planet of Birds, we have been observing the great tit in its natural habitats for over four decades, documenting its foraging strategies, breeding behavior, and interactions with its environment. What stands out most is its ability to thrive in a changing world, adjusting its diet, nesting habits, and even migration patterns to new conditions. Whether in dense forests, urban parks, or suburban gardens, the great tit continues to prove itself as one of nature’s greatest survivors, offering a glimpse into the extraordinary intelligence and adaptability of birds.

Further reading