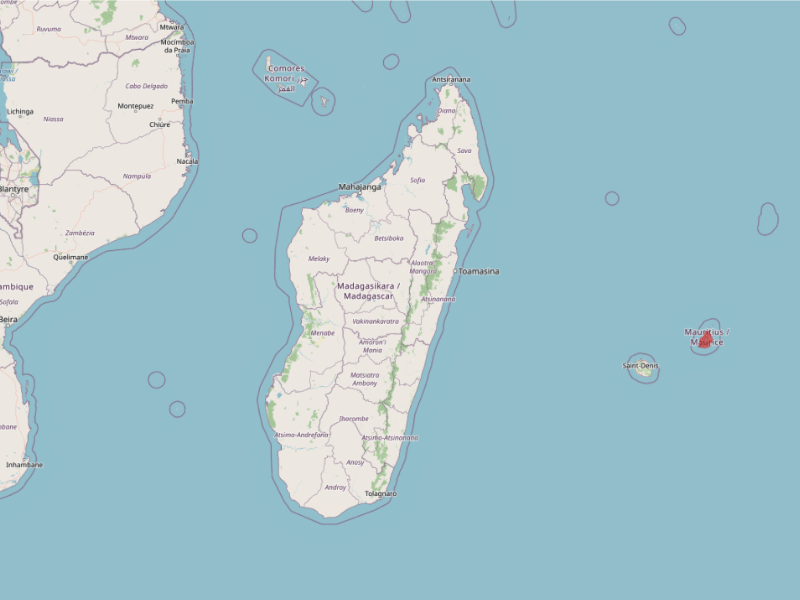

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was a flightless bird endemic to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Driven to extinction by the late 1600s, it was killed off by human activities, including overhunting, habitat destruction, and the introduction of non-native species that preyed on its eggs. The dodo is one of the earliest recorded cases of a species gone extinct due to human actions, making it a key example in conservation discussions and highlighting the vulnerability of island ecosystems.

| Common name | Dodo |

| Scientific name | Raphus cucullatus |

| Order | Columbiformes |

| Family | Columbidae |

| Genus | Raphus |

| Discovery | First documented by Dutch sailors in 1598 (Admiral Wybrand van Warwijck) |

| Identification | Large, flightless bird with a bulky body, strong legs, small vestigial wings, and a hooked beak |

| Lifespan | Estimated 10-20 years in the wild |

| Range | Endemic to Mauritius, last confirmed sighting on Île d’Ambre |

| Migration | Non-migratory, but may have moved between different habitat zones |

| Habitat | Primarily dry lowland forests and coastal woodlands, occasional presence in highland regions |

| Diet | Fruits, seeds, roots, possibly small invertebrates |

| Conservation status | Extinct; last confirmed sighting in 1662, possibly survived until 1690 |

| Why extinct | Overhunting, habitat destruction, and invasive species (pigs, rats, monkeys) preying on eggs |

Discovery

The dodo was first documented by Dutch sailors in 1598, when an expedition led by Admiral Wybrand van Warwijck arrived on Mauritius. The sailors described a large, flightless bird that was unafraid of humans, making it easy to catch. Early accounts suggested the species was abundant, though its population was likely already restricted to certain areas.

The bird was first scientifically described in the 17th century, but its rapid extinction meant that formal classification efforts were delayed. In 1634, Sir Thomas Herbert provided one of the most detailed early descriptions, and in 1662, Volquard Iversen, a marooned sailor, recorded the last reliable sighting of the bird. Later reports, such as those from Benjamin Harry in 1681, are now considered unreliable.

Recognition and classification

For centuries after its extinction, knowledge about the dodo came from paintings, written descriptions, and scattered fossil remains. The first scientific attempt to classify the species was made by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, when he included it in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae under the genus Didus with the species name Didus ineptus. This classification, however, was based on second-hand descriptions and artistic depictions rather than direct examination of physical remains.

Johann Friedrich Gmelin, in his 1788 expanded edition of Systema Naturae, retained Linnaeus’ Didus ineptus designation but, like Linnaeus, had no access to dodo fossils. As more skeletal evidence emerged in the 19th century, it became clear that the dodo was closely related to pigeons, leading to the abandonment of Didus in favor of a more accurate classification.

In 1832, Johann Georg Wagler reassigned the dodo to the genus Raphus, which remains in use today. By the mid-19th century, Hugh Edwin Strickland and Alexander Gordon Melville published The Dodo and Its Kindred, the first detailed scientific study based on fossil evidence. Their work confirmed the dodo’s relationship to pigeons and doves, establishing its placement within the family Columbidae.

Modern studies and discoveries

Recent studies using bone histology have provided new insights into the dodo’s life history. Analysis of growth rings in its bones suggests that the dodo underwent annual molting cycles and reached full adult size within one year. This research also indicates that the species likely timed its breeding season to coincide with Mauritius’ weather patterns, ensuring that food availability supported the growth of hatchlings.

Further discoveries have also challenged previous assumptions about the dodo’s habitat preferences. In 2006, an associated dodo skeleton was found in a Mauritian lava cave, suggesting that the bird may have occupied a wider range of environments beyond lowland forests. This finding indicates that the dodo was possibly more adaptable than previously thought.

Today, the dodo is classified within the family Columbidae (pigeons and doves) under the genus Raphus. Advances in DNA analysis have further confirmed that its closest living relative is the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), reinforcing its evolutionary connection to island-dwelling pigeons.

Identification

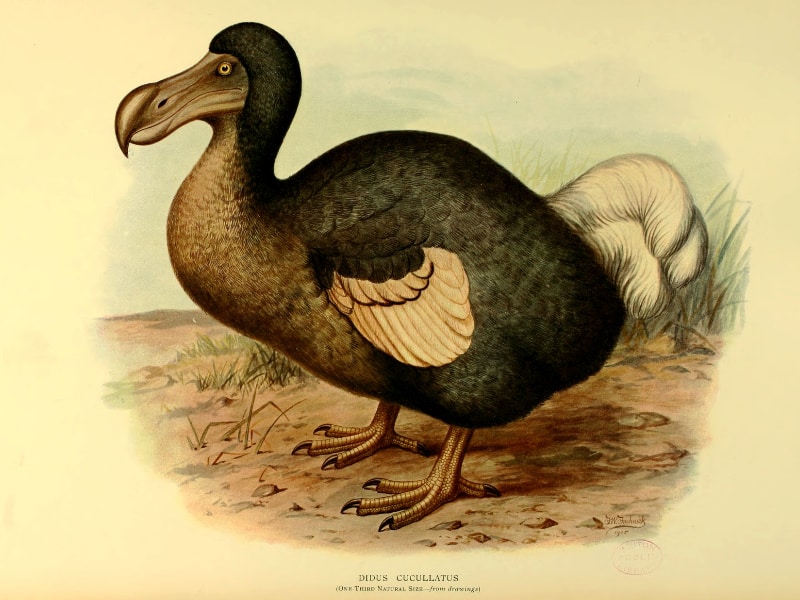

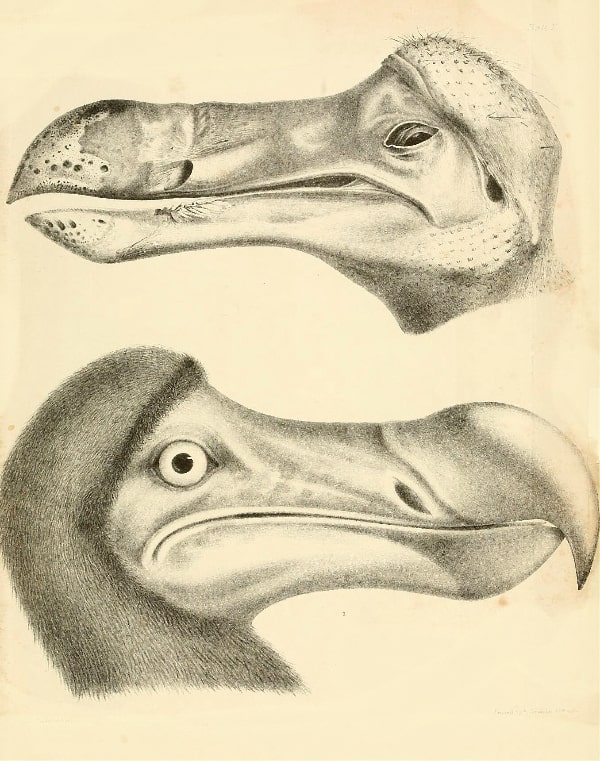

The dodo was a large, flightless bird measuring approximately 70-90 centimeters (2.3-3 feet) in height and weighing between 11 and 18 kilograms (24-40 pounds), though weight likely varied seasonally. It had small, vestigial wings that spanned an estimated 20-25 centimeters (7.9-9.8 inches) when extended, making flight impossible. However, these wings may have been used for balance or courtship displays. The bird had a large, hooked beak, which may have helped in foraging tough plant material or defending itself from competitors. Its sturdy legs were well-adapted for terrestrial movement.

Descriptions of the dodo’s plumage vary among historical sources. Some reports describe it as grayish-brown, while others suggest a more varied coloration with lighter or downy feathers. Juveniles were likely covered in soft, fluffy down, similar to many pigeon species, before developing adult plumage. A tufted tail of curled feathers was a distinctive feature in many contemporary paintings, though artistic depictions are inconsistent.

Roelant Savery’s paintings, including this 1626 artwork above, have heavily influenced modern reconstructions of the dodo. Later owned and documented by the ornithologist George Edwards, it became widely known as “Edwards’ Dodo.” However, like many of Savery’s works, this depiction may not be entirely accurate, as it was likely based on captive specimens (possibly overfed) or on second-hand descriptions that misrepresented the bird’s true appearance in the wild.

There is limited direct evidence of sexual dimorphism in the dodo. However, some fossil studies suggest that males may have been slightly larger than females, which is a common trait in pigeon species. Without complete sexed skeletons, the extent of these differences remains speculative.

Vocalization

There are no confirmed records of the dodo’s vocalizations. However, as a member of the Columbidae family (pigeons and doves), it may have produced cooing, grunting, or low-frequency calls similar to its closest relatives. Given its terrestrial nature, vocal communication may have played a role in territorial behavior or mate attraction.

Range

The dodo was endemic to Mauritius, an island in the Indian Ocean, and was never found anywhere else. While its primary range included dry lowland forests, fossil evidence suggests that its distribution may have been more restricted than previously thought. The last confirmed report of the dodo was from the offshore islet Île d’Ambre in 1662, recorded by Volquard Iversen. However, statistical models suggest that small, isolated populations may have persisted until around 1690.

Migration

There is no evidence that the dodo migrated. As an island-endemic species, the dodo was entirely flightless and restricted to Mauritius. Unlike some birds that move seasonally to track food sources, dodos likely adapted to the island’s climate and resource fluctuations by adjusting their breeding cycles and foraging behaviors rather than migrating.

Some researchers suggest that dodos may have moved between different habitats within Mauritius, such as lowland forests, coastal areas, and possibly highland regions (as suggested by the 2006 lava cave discovery). However, these would have been localized movements rather than true migration.

Habitat

The dodo primarily inhabited dry lowland forests and coastal woodlands, where it foraged for fallen fruits, seeds, and other plant material on the forest floor. It likely played a role in seed dispersal for native trees, helping maintain the island’s ecosystem.

Recent discoveries, including the 2006 finding of a dodo skeleton in a highland lava cave, challenge the assumption that dodos were exclusively lowland dwellers. This suggests that the species may have occupied a wider range of environments, including higher-altitude regions, at least temporarily.

Although historical accounts often depict the dodo as widespread, evidence suggests that it did not inhabit the entire island but was concentrated in specific regions where food was abundant and competition was low. The presence of remains in Mare aux Songes, a swampy area in southeastern Mauritius, further indicates that dodos may have also frequented wetland environments, possibly for access to water and additional food sources.

Behavior

The dodo was a ground-dwelling, flightless bird that evolved in the absence of natural predators. As a result, it likely lacked strong defensive behaviors and was tame and unwary of humans, making it an easy target for sailors and early settlers. Observations from early travelers suggest that dodos may have been social birds, possibly forming loose groups while foraging.

Bone histology studies indicate that dodos experienced seasonal growth patterns, suggesting that their behavior, including molting and breeding cycles, was influenced by Mauritius’ climate. Their strong legs and robust beaks indicate that they were well-adapted for terrestrial foraging, likely spending much of their time searching for food on the forest floor.

Breeding

The dodo likely laid a single egg per breeding cycle, which it nested on the ground. Before the arrival of humans, there were no mammalian predators on Mauritius, so the dodo’s reproductive strategy did not account for egg predation. However, after the introduction of rats, pigs, and monkeys, dodo eggs became highly vulnerable, which accelerated the species’ decline.

Based on comparisons with pigeons, its closest relatives, dodos may have engaged in monogamous pair bonding, with both parents contributing to egg incubation and chick-rearing. However, due to the rapid extinction of the species, these details remain speculative.

Lifespan

The exact lifespan of the dodo is unknown, as no direct studies exist. However, estimates suggest that it lived between 10 and 20 years in the wild. Bone growth analysis indicates that dodos grew rapidly, reaching adult size within a year, which is consistent with birds adapted to seasonal environments.

Diet

The dodo primarily consumed fruits, seeds, and roots, and may have supplemented its diet with small invertebrates. Fossilized gut contents and historical reports suggest that palm fruits and other native Mauritian plants were key components of its diet.

Studies indicate that the dodo played a role in seed dispersal, particularly for species like the Tambalacoque tree (Sideroxylon grandiflorum), sometimes called the “dodo tree.” It has been hypothesized that dodos helped break down the hard seeds of this tree, aiding in their germination. However, this idea remains debated, as other animals may have also contributed to seed dispersal.

The structure of the dodo’s beak and skull suggests that it may have been able to crack hard seeds or dig for roots, making it an opportunistic feeder rather than a specialist. This adaptability would have allowed it to thrive in Mauritius’ seasonal environment, where food availability fluctuated throughout the year.

Culture

The dodo has become one of the most recognizable symbols of extinction, with its name often used metaphorically to describe something obsolete or irreversibly lost. The phrase “as dead as a dodo” is widely used in the English language to signify complete extinction.

The bird gained literary fame through its appearance in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), where the Dodo character is believed to be a self-reference by Carroll, whose real name was Charles Dodgson. Since then, the dodo has been depicted in countless books, films, and artworks, solidifying its image as a clumsy, almost comical creature – a perception that does not necessarily reflect its true nature.

In the modern entertainment industry, the dodo has been featured in animated films, most notably in the Ice Age series (2002-2016). In the first film, a group of dodos is humorously portrayed as irrational and self-destructive, leading to their own extinction. While exaggerated for comedic effect, such portrayals have contributed to the dodo’s cultural reputation as a foolish, ill-fated bird.

In Mauritius, the dodo remains a national symbol, appearing on the country’s coat of arms, stamps, coins, and souvenirs. Despite its tragic extinction, the dodo’s legacy has helped raise awareness about conservation efforts, particularly for other island-endemic species threatened by human activity and invasive species.

Scientific reconstructions of the dodo continue to evolve, with new discoveries refining our understanding of its appearance, behavior, and ecological role. While early artistic depictions, such as those by Roelant Savery, shaped the public’s perception of the bird, modern research suggests that these images exaggerated certain features, particularly its bulk and posture.

Threats and extinction

The dodo’s extinction was primarily caused by human activities, including overhunting by sailors and the introduction of invasive species such as pigs, rats, and monkeys, which preyed on its eggs. While early accounts often blamed direct hunting, recent studies suggest that habitat destruction and invasive predators played an even greater role in the species’ decline.

By the 1640s, the dodo population had already been severely reduced, and the bird was likely functionally extinct, meaning that even if a few individuals remained, the population was no longer viable. The last confirmed sighting occurred in 1662, recorded by Volquard Iversen on Île d’Ambre. However, unconfirmed reports suggest that small, isolated populations may have persisted until the late 1600s, with some statistical models estimating survival until around 1690.

Who killed the last dodo?

There is no documented record of who killed the last dodo, but there is no doubt that humans were responsible for its extinction. The dodo’s decline was not the result of a single event but a combination of relentless hunting, habitat destruction, and predation by invasive species introduced by humans. The last confirmed report in 1662 does not describe a dodo being hunted but rather an observation of a dwindling population. However, given that dodos were frequently killed for food and that their eggs were repeatedly destroyed by invasive animals, it is likely that the last dodo either fell victim to human hunting, succumbed to starvation due to habitat loss, or failed to reproduce due to predation of its eggs.

While we may never know the exact fate of the final individual, the species’ extinction was entirely human-driven. The destruction of its ecosystem, the introduction of non-native predators, and direct exploitation sealed its fate long before the last bird vanished. No conservation efforts were made before the dodo’s extinction, as the concept of species conservation did not exist at the time. Its disappearance served as one of the earliest warnings of human-driven extinction, later influencing modern conservation efforts for other endangered species.

Similar species

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) belonged to the Columbidae family, which includes modern pigeons and doves. Despite its unique, flightless appearance, its closest relatives were other island-dwelling pigeons, particularly those that evolved under similar ecological pressures.

Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria)

The Rodrigues solitaire, a flightless bird endemic to Rodrigues Island, was the dodo’s closest known relative. Like the dodo, it evolved in an isolated environment without predators, leading to flightlessness and a large body size. However, the Rodrigues solitaire was more territorial and aggressive, with wing-knobs used for combat. It went extinct in the late 1700s, likely due to hunting and introduced species, following a similar fate to the dodo.

Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica)

The Nicobar pigeon is the dodo’s closest living relative. Unlike the dodo, it is fully capable of flight, but shares similar traits such as ground foraging and a reliance on island habitats. Found in the Nicobar Islands, Southeast Asia, and parts of the Pacific, this species offers valuable insight into how the dodo’s ancestors might have looked before becoming flightless.

Conclusion

The dodo’s extinction is one of the earliest recorded cases of human-driven species loss, serving as a powerful reminder of how fragile island ecosystems can be when faced with hunting, habitat destruction, and invasive species. For centuries, the dodo was portrayed as a clumsy, foolish bird, an image reinforced by literature and exaggerated artistic depictions. However, modern research paints a different picture – one of a highly specialized island species that thrived in an environment free of predators until humans arrived.

At Planet of Birds, we recognize the dodo not just as a symbol of extinction but as a warning about the dangers of unchecked environmental destruction. Its story is not just history – it’s a lesson for the present. Many other island species today face the same threats that wiped out the dodo, and while we cannot bring the dodo back, we can act now to protect other vulnerable species from meeting the same fate.

The dodo’s legacy continues to influence conservation science, highlighting the need for early intervention to prevent extinctions. By studying the dodo and its ecosystem, we gain valuable insights into how island species evolve and how they can be protected today. The next time you hear the phrase “dead as a dodo,” remember that the dodo was not inherently doomed, it was a victim of rapid environmental change. Let it be a call to action to ensure that other species do not suffer the same fate.

Further reading