The black stilt (Himantopus novaezelandiae) is one of the world’s rarest wading birds, endemic to New Zealand. Once widespread across both islands, its population has faced severe declines due to habitat loss, predation, and hybridization with the closely related pied stilt.

| Common name | Black stilt |

| Scientific name | Himantopus novaezelandiae |

| Alternative name | Kaki (Maori language) |

| Order | Charadriiformes |

| Family | Recurvirostridae |

| Genus | Himantopus |

| Identification | Entirely black plumage, long pink legs, slender black bill |

| Range | South Island, New Zealand |

| Migration | Non-migratory |

| Habitat | Braided riverbeds, wetlands, and shallow lakes |

| Diet | Aquatic invertebrates, small fish, larvae |

| Conservation status | Critically endangered |

Discovery

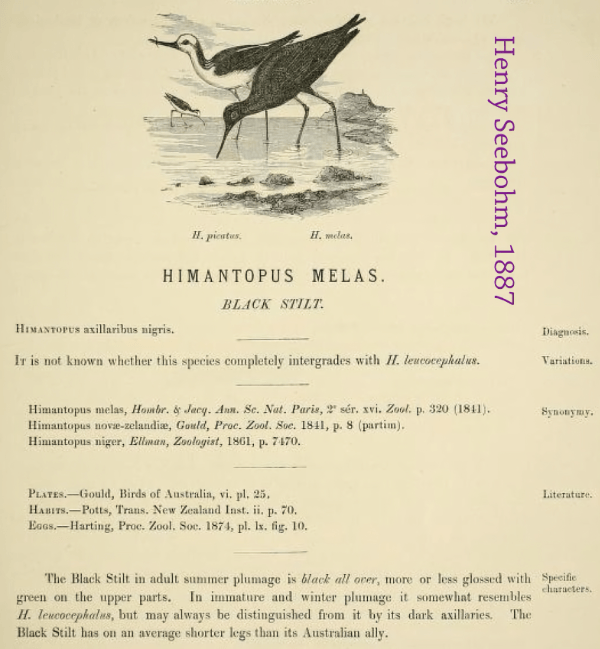

The black stilt, a member of the family Recurvirostridae, was first formally described by Captain Frederick Wollaston Hutton in 1871. Early ornithologists noted confusion regarding its classification, primarily due to the similarity between juvenile black stilts and the pied stilt (Himantopus leucocephalus). This led to debates about whether it was a distinct species or simply a color morph or immature form of the pied stilt.

By the 1880s, naturalists like Walter Buller recognized the black stilt as a distinct species, noting its darker plumage and shorter legs compared to the New Zealand pied stilt. Buller described it as less gregarious, typically associating in pairs rather than flocks, and preferring dry shingle-beds over the lagoons and marshy grounds favored by pied stilts.

Henry Seebohm further speculated in 1887 that the black stilt might have emigrated from either Chile or Australia, evolving its distinctive black nuptial plumage as a result of sexual selection. These early insights highlighted both the bird’s rarity and its complex evolutionary history. By the early 20th century, the black stilt was widely recognized as a distinct, though increasingly rare, species.

Identification

The black stilt is distinguished by its entirely black plumage, long pink legs, and slender black bill. Adults typically measure between 40 and 44 cm (16-17 inches) in height, with a wingspan of 75 to 80 cm (30-31 inches). They weigh approximately 220 to 250 grams (7.7-8.8 oz). There is no significant sexual dimorphism in this species; males and females are similar in size and appearance, though males may be slightly larger.

Juveniles are notably different, displaying white underparts and greyish tones on the head and throat. As they mature, these lighter markings gradually darken until the full black adult plumage is achieved.

Vocalization

The black stilt produces a sharp, repetitive yapping call, often compared to the bark of a small dog. This call is frequently heard during flight and when the bird is disturbed, serving as both a territorial warning and a means to deter predators. Vocal activity intensifies during the breeding season, particularly when defending nests and chicks from intruders.

Range and habitat

Historically, the black stilt was distributed across both the North and South Islands of New Zealand. However, due to significant population declines in the 20th century, the species is now confined to the South Island, with its stronghold in the upper Waitaki basin in the Mackenzie District.

The black stilt favors braided riverbeds, particularly those with shingle banks and sparse vegetation, which provide ideal nesting and foraging grounds. Key river systems where they are found include the Ahuriri, Tekapo, Tasman, Godley, Dobson, and Hopkins rivers. In addition to riverbeds, they also utilize shallow wetlands, tussockland margins, and kettle ponds near Lakes Ohau and Tekapo for feeding. These habitats offer abundant aquatic invertebrates and small fish, crucial for their diet.

The species’ habitat preferences make them highly vulnerable to changes in water flow from hydroelectric developments, invasive plant species encroaching on nesting sites, and human disturbance in riverbed areas.

Behavior

Black stilts are monogamous, typically forming lifelong pair bonds. They are solitary by nature, preferring to nest and forage alone or in pairs rather than in flocks, unlike their close relative, the pied stilt. This solitary behavior extends to their territoriality, especially during the breeding season when pairs aggressively defend their nesting sites from intruders.

Historical observations indicate that both black and pied stilts were once abundant on riverbeds and harbor islands. The vigilance of these birds was noted to be particularly striking, with their harsh alarm calls quickly alerting other wildlife, such as ducks, to potential threats. While pied stilts remain common and gregarious today, such encounters with the solitary black stilt have become increasingly rare due to their declining population.

They are highly vigilant and display a range of defensive behaviors when their nests or young are threatened. Parents often attempt to distract potential predators with clever tactics, including feigning injury. However, unlike pied stilts, black stilts are less likely to perform these distraction displays during the early stages of incubation, reserving them for when chicks are close to hatching. When disturbed, chicks exhibit remarkable camouflage skills, hiding behind stones or vegetation to evade detection.

Outside the breeding season, black stilts are mostly sedentary, with limited movement between their preferred riverbeds and nearby wetlands for feeding.

Breeding

Breeding occurs early in the season, starting as early as August, with the peak period between September and December. Black stilts select nesting sites on sandy or gravel riverbeds, often on the banks of small streams and side channels of major rivers. Their nests are minimalist, typically consisting of a shallow scrape in the ground, sometimes lined with small stones or bits of vegetation. Occasionally, nests may be placed on driftwood or grassy patches near water, but they are never far from a water source.

The female lays three to four eggs per clutch. Both parents share incubation duties, with shifts changing every few hours. The incubation period lasts approximately 25-28 days. If a clutch is lost early in the season, pairs may re-nest.

Chicks are precocial, able to leave the nest and run within hours of hatching. However, they remain dependent on their parents for guidance and protection during the fledging period, which can last between 39 and 55 days – longer than the pied stilt’s fledging period. This extended period increases their vulnerability to predation.

Black stilts typically begin breeding at three years of age, although some may start earlier. The average lifespan in the wild is about 6.8 years, with some individuals documented living over a decade.

Diet

The black stilt’s diet consists primarily of aquatic invertebrates, including insect larvae, mollusks, crustaceans, and worms. They also consume small fish and occasionally plant material such as seeds and aquatic vegetation, though animal prey forms the bulk of their intake. Foraging typically occurs in shallow waters along river edges, wetlands, and lake margins, where they use their slender, pointed bills to pick prey from the water surface or probe into soft substrates.

Their foraging behavior is both deliberate and adaptable. While they often wade through shallow water, they are also known to feed on exposed mudflats or gravel bars when water levels recede. During the breeding season, adults increase their foraging activity to meet the higher energy demands of incubating eggs and feeding chicks. Chicks feed on smaller invertebrates found near nesting sites and gradually expand their foraging range as they grow.

Seasonal variations and habitat conditions influence food availability, with fluctuations in water levels due to hydroelectric projects or droughts posing a challenge to their foraging efficiency.

Culture

The Maori people have long been aware of the black stilt, giving it the name Kaki. Despite this recognition, the bird does not appear to play a significant role in traditional Maori myths, legends, or cultural practices, unlike many other native bird species in New Zealand.

In contemporary New Zealand, the Black Stilt has become a powerful symbol of the country’s unique biodiversity and the challenges of species conservation. It is emblematic of successful conservation efforts, with Kaki recovery programs becoming a source of national pride. The bird is frequently used in educational campaigns and environmental initiatives to raise awareness about endangered species and the importance of habitat preservation.

Threats and conservation

The black stilt is one of the rarest wading birds in the world and is classified as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List. The species has faced a dramatic population decline due to multiple, interconnected threats. The most significant of these is predation by introduced mammals, including cats, stoats, ferrets, and weasels. Originally brought in to control rabbit populations in the 19th century, these predators have had a devastating impact on native bird species, particularly ground-nesting birds like the black stilt.

Habitat loss and degradation are additional major threats. Hydroelectric development in the South Island has altered river flow patterns and flooded traditional nesting sites, while agricultural expansion has led to wetland drainage and the invasion of non-native plant species. Human disturbances, such as recreational activities in riverbeds and wetlands, further disrupt breeding behaviors and increase the risk of nest abandonment.

Hybridization with the pied stilt presents another challenge. As black stilt numbers declined, interbreeding with the more common pied stilt became more frequent, threatening the genetic integrity of the species. Efforts to prevent hybridization have become a key component of conservation strategies.

Conservation efforts for the black stilt intensified in 1981 when the wild population plummeted to just 23 individuals. A comprehensive recovery program was launched, focusing on captive breeding, predator control, habitat restoration, and public engagement. Captive-bred birds are regularly released into the wild, and predator trapping around nesting sites has been ongoing since 1997. Water levels in managed wetlands are manipulated to create optimal feeding conditions, and there are continuous efforts to prevent hybridization by monitoring mixed-species pairs.

By 2012, the free-living population had increased to approximately 130 individuals, largely due to the success of captive breeding and release programs. As of 2023, the wild population is estimated at 169 adult individuals, reflecting ongoing conservation progress. However, the species remains critically endangered, and its survival depends on sustained conservation actions. Feasibility studies for establishing a second population on a predator-free island have been conducted, but finding a suitable release site remains a challenge.

Similar species

The pied stilt (Himantopus leucocephalus) is the species most closely resembling the black stilt. While the black stilt is entirely black, the pied stilt features contrasting black-and-white plumage, with a white face, neck, and underparts, and black wings and back. Both species share similar body shapes, long pink legs, and slender black bills, making them difficult to distinguish at a distance, especially when juvenile black stilts display lighter plumage. Behaviorally, the pied stilt is more gregarious, typically seen in flocks, whereas the black stilt tends to be solitary or found in pairs.

Further reading

At Planet of Birds, we’ve been following the plight of the black stilt for over four decades. This article draws from a combination of historical records, conservation reports, and firsthand observations gathered throughout years of dedicated research. From the early days of population monitoring in the 1980s to the more recent successes of captive breeding programs, we’ve witnessed the challenges and triumphs faced in the fight to save one of the world’s rarest birds.

We believe that the black stilt will survive, provided that predation by introduced mammals can be effectively managed. While the species may continue to rely on partially artificial environments, such as predator-controlled habitats and captive breeding facilities, it has shown remarkable resilience. We are optimistic that with sustained conservation efforts, the Kaki will extend its presence in the wild, even if it means living in what could be described as a carefully managed “day care center.”

For readers interested in exploring more about the black stilt and conservation efforts in New Zealand, we recommend the following resources:

- G. P. Wallis (1999). Genetic Status of New Zealand Black Stilt (Himantopus Novaezelandiae) and Impact of Hybridisation.

- R. J. Pierce (1986). Black Stilt (Endangered New Zealand Wildlife Series). John McIndoe & New Zealand Wildlife Service.

- R. J. Pierce (1984). Plumage, Morphology and Hybridisation of New Zealand Stilts Himantopus spp. Notornis.

- New Zealand Department of Conservation: Black stilt/Kaki.