Baer’s pochard (Aythya baeri) is a critically endangered, medium-sized diving duck that was once widespread across East and Southeast Asia. Due to extensive habitat destruction and overhunting, its population has plummeted over the past few decades, making it one of the rarest ducks in the world.

| Common name | Baer’s pochard |

| Scientific name | Aythya baeri |

| Order | Anseriformes |

| Family | Anatidae |

| Genus | Aythya |

| Identification | Medium-sized diving duck with a dark green head, white flanks, and dark back; soft, low quack often heard during breeding season |

| Range | Historically from eastern Russia to Southeast Asia; now mostly in central-east China |

| Migration | Partial migrant; some populations now remain year-round in China |

| Habitat | Freshwater lakes, ponds, reservoirs, and fishponds with dense vegetation |

| Diet | Insects and small fish in breeding season; plants and seeds in winter |

| Conservation status | Critically endangered |

Discovery

Baer’s pochard was first described in 1863 by Gustav Radde, a German naturalist and explorer, who encountered the species in the Russian Far East. The species was named in honor of Karl Ernst von Baer, a prominent Baltic German naturalist, biologist, and explorer known for his pioneering work in embryology and contributions to zoology and geography. Baer’s extensive research in the Russian Empire influenced Radde’s decision to name the species after him.

Baer’s pochard belongs to the family Anatidae, which includes ducks, geese, and swans. It is part of the genus Aythya, a group of diving ducks characterized by their ability to forage underwater. The genus Aythya comprises twelve extant species, including the well-known tufted duck (Aythya fuligula) and the ferruginous duck (Aythya nyroca), with which Baer’s pochard is often confused.

Fossil evidence suggests that Aythya has a long evolutionary history. Aythya shihuibas was described from the Late Miocene of China, highlighting the genus’s ancient presence in Asia. Additionally, an undescribed prehistoric species from Early Pleistocene fossil remains found in Dursunlu, Turkey, may be related to a paleosubspecies of a currently existing species. Some fossils previously attributed to Aythya, such as Aythya arvernensis, have been reclassified into the genus Mionetta, while Aythya chauvirae likely represents remains of at least two species, one of which may not be a diving duck.

Identification

Baer’s pochard is a medium-sized diving duck measuring about 41-46 cm (16-18 inches) in length, with a wingspan of approximately 70 cm (27.6 inches). It has a robust body typical of diving ducks in the Aythya genus.

Males are distinguished by a dark metallic green head and neck, which transitions to black on the lower neck. A small white spot is present on the chin. The mantle is black down the center, with ruddy chestnut sides matching the breast. The scapulars are very dark brown with fine speckling, while the back, rump, tail, and upper tail-coverts are black. The breast is ruddy chestnut, fading into brown on the sides and flanks, sharply contrasting with the pure white abdomen. The speculum is white, bordered by a black band formed by the tips of the secondary feathers. Primaries are dark brown on the outer web and pearl gray on the inner web.

In flight, Baer’s pochard displays a wing pattern similar to the ferruginous duck (Aythya nyroca), but the white upperwing band does not extend as far onto the outer primaries. Males have pale, whitish eyes and a blue-gray bill.

Females are similar in appearance but less glossy, with a chestnut patch near the base of the bill and duller chestnut on the breast. The head lacks a nuchal tuft, and there is a noticeable contrast between the darker head and the warm brown breast, differentiating it from both ferruginous duck and tufted duck. The foreflanks are white, providing additional contrast. Female eyes are darker, often gray or brown, and the bill and feet are less vibrant than in males. Older females may have paler eyes, occasionally appearing whitish.

Juveniles resemble females but have a more chestnut-tinged head with a darker crown and hindneck. They lack a defined loral patch, and their overall plumage is slightly more muted compared to adults.

Vocalization

Baer’s pochard has a soft, low quack, more frequently heard during the breeding season. While generally quiet, males may produce low grunting or whistling sounds as part of courtship displays.

Range and habitat

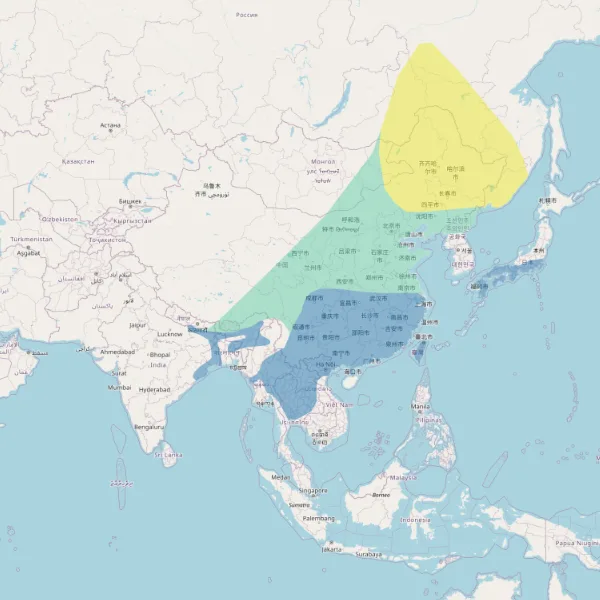

Historically, Baer’s pochard was widespread across East and Southeast Asia, breeding primarily in the Amur and Ussuri basins of Russia and northeastern China. It migrated south to winter in eastern and southern mainland China, India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar.

In the past, Bangladesh supported between 1,000 and 2,000 individuals, while Myanmar hosted 1,000 to 1,500. However, these populations have sharply declined, with recent counts in Bangladesh recording only 17 individuals. Myanmar, Thailand, and other regions have seen similar decreases, with many former strongholds now reporting rare or absent sightings.

The species is now rare or absent in Myanmar, Japan, North and South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Nepal, Bhutan, Thailand, Vietnam, and Mongolia. In Thailand, small numbers are still regularly recorded at Bung Khong Long, the only site with consistent double-figure counts. In Lao PDR, only a single confirmed record exists, and in Vietnam, the species has become very rare in recent years.

Today, Baer’s pochard’s range is mostly limited to isolated wetlands in China, where the majority of the remaining population is found. Recent studies have identified new breeding sites significantly south of its historical range, particularly in the provinces of Hebei, Henan, Shandong, Jiangxi, and Hubei.

All six confirmed breeding sites discovered since 2000 lie outside the previously recognized IUCN breeding range, with the southernmost site located about 1,400 km further south than historically documented. Additionally, some former wintering areas, such as the central Yangtze region, are now used as breeding grounds, reflecting shifts in habitat use.

Baer’s pochard inhabits freshwater lakes, ponds, and reservoirs with dense aquatic vegetation. In Liaoning, China, it can be found in coastal wetlands and forest-surrounded ponds. It has also adapted to artificial and fragmented habitats, including fishponds, reservoirs, and even urban wetlands, where dense vegetation provides cover and abundant food resources. It prefers areas with rich plant life, which provide cover and abundant food resources.

Migration

The majority of Baer’s pochard populations migrate to winter in eastern and southern China, northeastern India, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Myanmar. However, recent studies indicate significant shifts in migration patterns, with the northernmost wintering sites now located 800 km further north than previously recorded, in regions like Beijing and Tianjin.

Smaller groups have been observed on passage or wintering in Mongolia, Japan, North and South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Vietnam, and the Philippines, though these occurrences have become increasingly rare in recent years. In some regions, traditional migratory stopovers have become year-round habitats, suggesting that certain populations may no longer migrate extensively. For example, sites in Hebei, Henan, and Jiangxi provinces are now used for both breeding and wintering, indicating a shift toward partial residency.

In many of these regions, the species is now considered a rare vagrant or has disappeared entirely due to significant population declines.

Behavior

Baer’s pochard is a diving duck, known for its strong swimming abilities and adept diving behavior. It can stay submerged for up to 40 seconds, using its powerful legs to propel itself underwater to forage in shallow, vegetation-rich wetlands. The species is generally shy and avoids areas with frequent human activity, preferring secluded wetlands for both feeding and breeding.

During the breeding season, Baer’s pochard forms pair bonds shortly after arriving at the breeding grounds. Males exhibit strong territorial behavior, guarding nesting areas and engaging in displays to deter rivals. Outside the breeding season, the species becomes more social and can be observed in small flocks, particularly during migration and at wintering sites.

Breeding

The breeding season begins in mid-April when males and females form pair bonds upon arrival at the breeding grounds. Egg-laying typically starts in May and continues into June, with clutch sizes ranging from 9 to 15 eggs. Nests are constructed in dense vegetation, often on tussocks or under shrubs, and occasionally float among branches.

Baer’s pochard sometimes nests in loose colonies alongside other waterfowl, such as the common pochard (Aythya ferina) and gadwall (Mareca strepera). Some females may lay eggs in the nests of these species, although this can be ineffective, as common pochards are known to reciprocate by laying their eggs in Baer’s pochard nests.

Incubation lasts between 23 and 28 days and is performed solely by the female. The male guards the nesting area and may assist in feeding the female. In undisturbed areas, ducklings that hatch first will remain near the nest until all eggs have hatched. However, if the nest is disturbed, parents may abandon unhatched eggs and move the hatchlings to a safer location.

Both parents care for the ducklings for two to three weeks, after which the young begin to dive and forage independently. Once the ducklings become self-sufficient, the adults leave to undergo their annual molt, while the juveniles form new flocks.

Diet

Baer’s pochard primarily feeds on aquatic plants, seeds, and small invertebrates. During the breeding season, its diet shifts to include more protein-rich food such as insects, mollusks, shrimps, small fish, and algae to support reproduction and chick development. In contrast, during migration and winter, it focuses more on aquatic vegetation and seeds. Foraging typically occurs in shallow waters rich in vegetation, where the species dives to access food sources below the surface.

Threats and conservation

Baer’s pochard, one of the rarest ducks in the world, has experienced a catastrophic population decline and is now classified as critically endangered due to a combination of habitat destruction, overhunting, and environmental degradation.

The primary threat is habitat destruction, particularly from the drainage of wetlands for agriculture, urban development, and fishing activities. The removal of large quantities of aquatic vegetation for fishing has lowered water levels at breeding grounds, significantly impacting reproductive success. Additionally, pesticide runoff and vegetation removal have disrupted local ecosystems, leading to poor water quality, weed overgrowth, and siltation—all of which reduce the suitability of habitats for Baer’s pochard and other waterbirds. Recent studies have also shown that many key habitats now overlap with urban areas, particularly in central-east China, increasing the risk of habitat fragmentation and human disturbance.

Overhunting has further exacerbated the decline. In regions like Bangladesh, poisoned bait has been used for hunting, posing a severe risk to Baer’s pochard and other species. In China, unconfirmed reports suggest that up to 3,000 individuals were being shot annually, though this figure may be exaggerated due to confusion between Baer’s pochard and mallards in Chinese translations.

Surveys in the Yangtze River basin revealed that nearly half of the total wintering wildfowl population was killed annually through netting, shooting, and poisoning. This indiscriminate hunting impacts all bird species in the area, including Baer’s pochard, as hunters often cannot distinguish between different Aythya species.

Egg collection from nests poses an additional threat. This not only reduces reproductive output but also disturbs breeding grounds, causing other nests to be abandoned. Furthermore, the retreat of the species into fragmented and unprotected wetlands has increased its vulnerability to both human disturbance and environmental degradation. The cumulative effects of these pressures have led to the species being absent or severely reduced across much of its former range.

Conservation efforts

Baer’s pochard has been uplisted to critically endangered by the IUCN due to the accelerating rate of its decline, particularly as observed in wintering grounds. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection, captive breeding, and the establishment of protected wetland reserves in China. Dedicated breeding programs aim to bolster wild populations and support reintroduction efforts. However, recent field studies have revealed that over 80% of Baer’s pochard habitats lie outside of protected areas, and more than 90% of suitable habitats are not covered by existing conservation networks.

The overlap of critical habitats with urban areas poses additional challenges, as many of these sites are exposed to human activity and development pressures. As a result, traditional protected areas may be insufficient to safeguard the species. Conservation strategies must include other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs), which can protect key habitats outside formal reserves.

Moreover, because Baer’s pochard’s range spans at least 15 countries along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, coordinated international cooperation is critical for its survival. Despite these initiatives, the species remains critically endangered, with the total population estimated at fewer than 1,000 individuals, and possibly as low as 250.

Despite ongoing initiatives, continued conservation action is essential to address habitat degradation, enforce hunting regulations, and restore wetland ecosystems critical to the survival of Baer’s pochard.

Similar species

Baer’s pochard is often confused with other Aythya species due to its size and coloration.

Ferruginous duck (Aythya nyroca)

The ferruginous duck is the most commonly mistaken species. Both are medium-sized diving ducks with chestnut-brown plumage, but Baer’s pochard males have darker, iridescent green heads and more pronounced white flanks compared to the ferruginous duck. In flight, Baer’s pochard displays a wing pattern similar to the ferruginous duck, though the white upperwing band does not extend as far onto the outer primaries.

Common pochard (Aythya ferina)

The common pochard shares a similar size and reddish-brown head coloration. However, common pochard males have a uniform reddish-brown head without the green sheen seen in Baer’s pochard, and their backs are lighter gray rather than dark.

Tufted duck (Aythya fuligula)

The tufted duck, especially the female, may be mistaken for Baer’s pochard due to their similar brown plumage. However, tufted ducks have a distinct black crest (or tuft) absent in Baer’s pochard, and their coloration patterns are more uniform.

Further reading

At Planet of Birds, we have been closely monitoring the status of Baer’s pochard across its range for over four decades. Our team has observed this critically endangered species in various locations throughout East and Southeast Asia, tracking its dramatic population decline and the shifting dynamics of its habitat. This article represents the culmination of extensive field observations, scientific research, and conservation studies, bringing together everything we’ve learned about Baer’s pochard in one comprehensive resource.

For those interested in exploring further, we recommend the following materials:

- (2022). Potential Suitable Habitat Distribution Shift and Conservation Gap of the Critically Endangered Baer’s Pochard (Aythya baeri). MDPI

- (2015). International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Baer’s Pochard. UNEP/CMS Secretariat.

- Richard Hearn (2015). The Troubled Baer’s Pochard Aythya Baeri: Cause for a Little Optimism?

- R. Hearn, X. Tao, G. Hilton (2013). A Species in Serious Trouble: Baer’s Pochard Aythya Baeri is Heading for Extinction in the Wild.

- S. U. Chowdhury, A. C. Lees, P. Thompson (2012). Status and Distribution of the Endangered Baer’s Pochard in Bangladesh.